COST OF RENT DAY - 2024

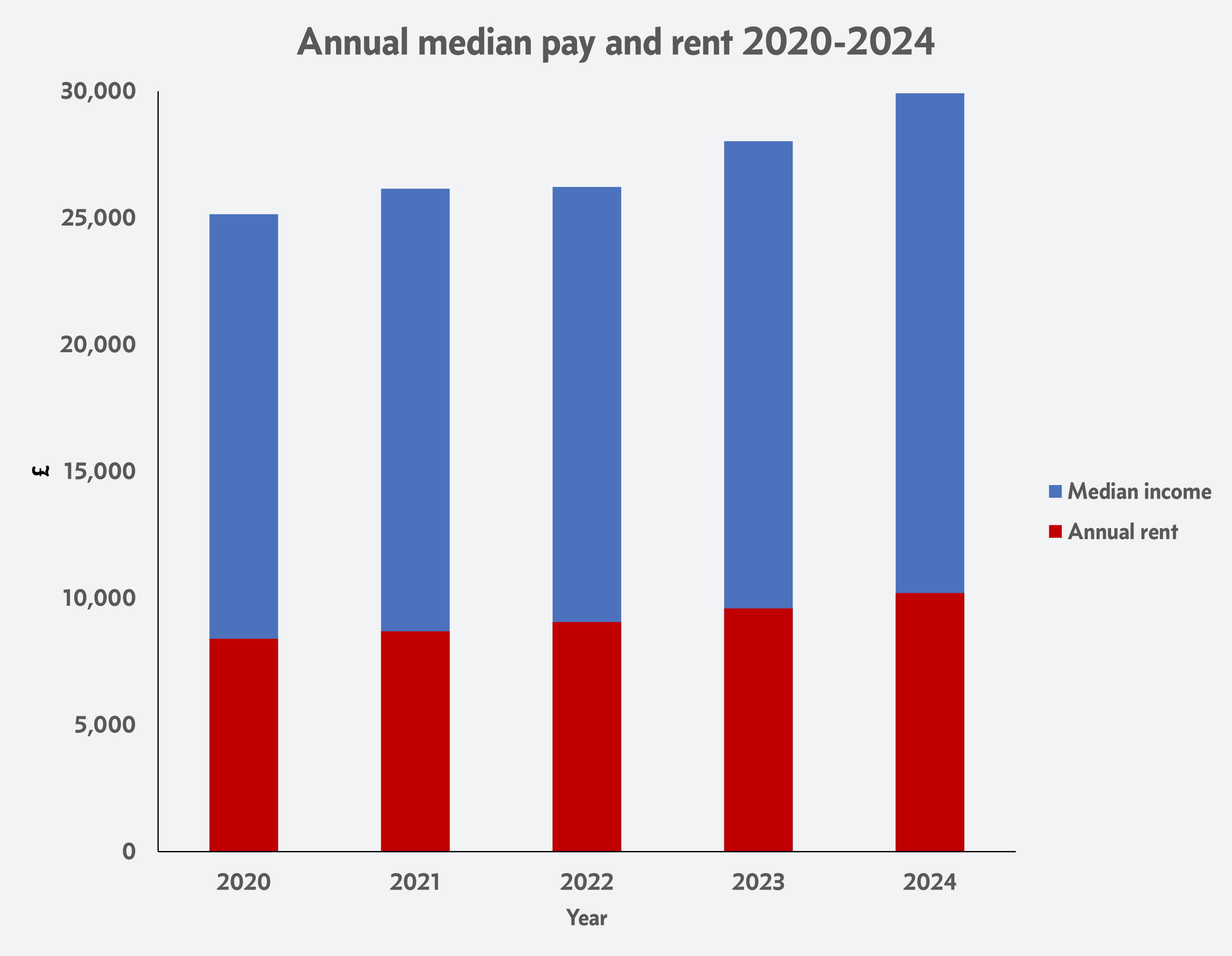

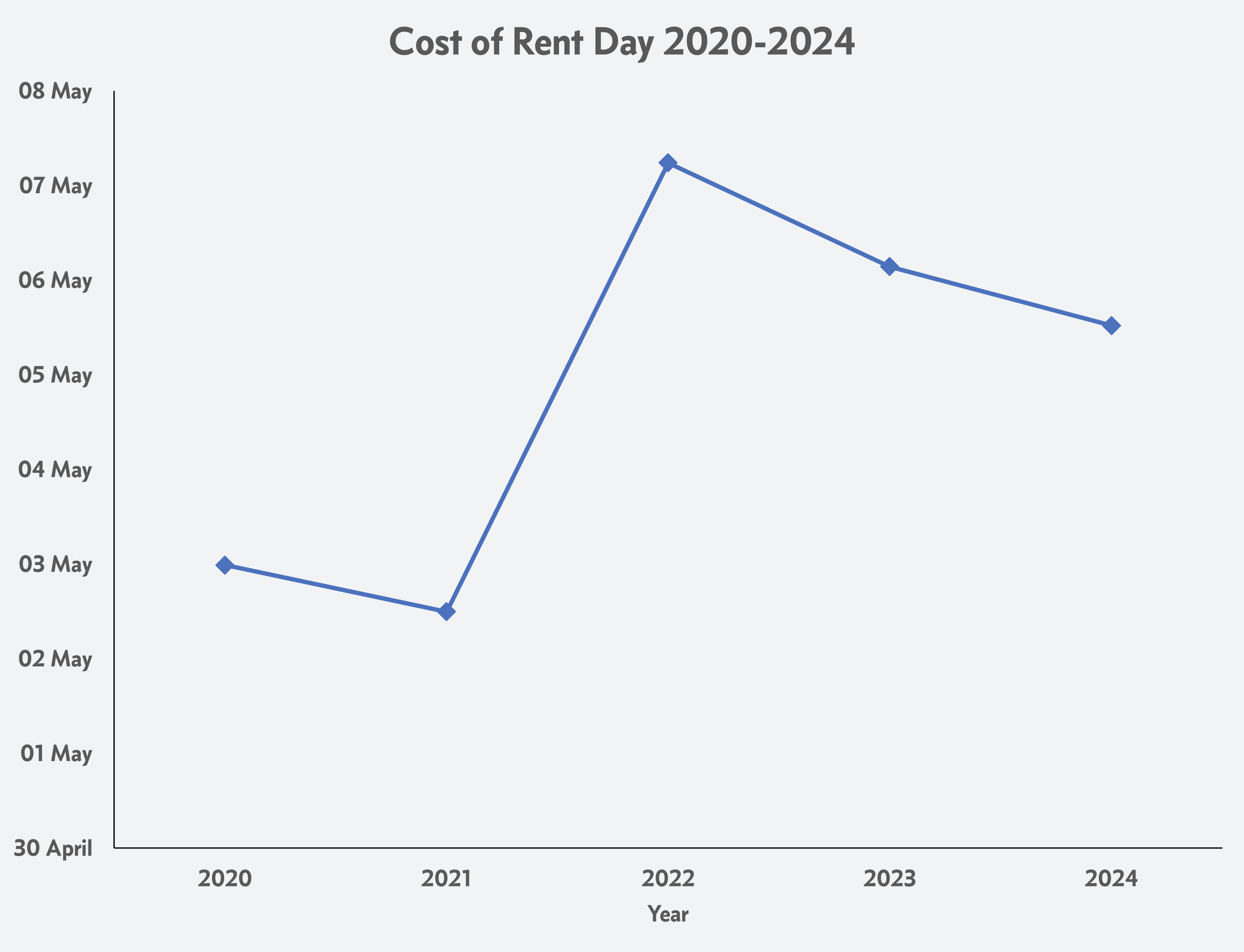

Renters in England worked 125 days for their landlords this year. The 5th of May is the first day they start working for themselves.

Cost of Rent falls on the 5th of May

English renters work 125 days of the year solely to pay their annual rent bill

This is a slight improvement on 2022 and 2023, but it's lateness emphasises the sheer severity of the housing crisis

Analysis of local areas shows Cost of Rent day is even later in cities and the South East, meaning that their higher salaries are not sufficient to compensate for the lack of homes

Kensington and Chelsea has the latest Cost of Rent day of 25th September and the average across London is 16th July.

Burnley has the earliest Cost of Rent day of 10th March and the average across the North East is 31st March.

Cost of Rent days have been calculated for 309 local areas, and 9 regions across England, enabling you to understand when the day falls in your specific locality.

Calculating Cost of Rent Day, and broader Cost of Housing Day is more challenging than it ought to be. As a basic recommendation the ASI proposes that the ONS should start producing consistent housing statistics that:

Cover the whole UK, not just England

Avoid local area data gaps

Enable a better understanding of gross annual incomes, and how they are spent on taxation, housing, and other key components (fuel and power, transport, food, recreation, hospitality, clothing, health, education etc.)

MPs from across parliament have provided comments in support of Cost of Rent Day, recognising the need to reduce the burden upon renters, particularly younger people.

It is now incumbent on policy makers to fix the housing crisis, in particular, addressing the shortage of supply of homes.

What is Cost of Rent Day?

Cost of Rent Day is the day when English renters stop paying rent and start putting their earnings into their own pocket.

This is a new measure the Adam Smith Institute has created to help translate the severity of the housing and rental crisis into simple terms that can be easily understood by all audiences.

The Adam Smith Institute lacks unanimous support for its ideas to solve the crisis. The ASI also fears many counterproductive solutions will be proposed by others in response to this measure. For example, Rent Controls have been consistently harmful in practice, which aligns with our economic analysis.

Nonetheless, Cost of Rent day provides a useful independent and non-partisan measure to simply highlight the problem and track tangible progress or further escalation over time.

For years the ASI has also calculated Tax Freedom Day and Cost of Government Day, showing that the tax burden is ever rising. After taxes and rents, very little is left.

While Rent Freedom Day is a new measure, the ASI has drawn upon the available ONS data sets to provide reliable records for a five-year period.

Policy implications - supply

The root problem driving Britain’s housing crisis is the lack of supply. Centre for Cities' analysis, notably the insights from Samuel Watling and Anthony Breach, highlights concisely the pivotal shifts in policy and practice that have led to the current situation.

Firstly, the post-World War II introduction of the Town and Country Planning Act in 1947 marked a significant turning point, establishing a discretionary planning system that has since been fundamental in shaping the UK's landscape. This system is characterised by its restrictive nature, significantly limiting the supply of new homes by requiring case-by-case decision-making for planning permissions, which slows down and reduces the development of new housing.

Furthermore, the decline in council house building, which began well before the policies of the 1980s, such as Right to Buy, contributed to a reduced overall housing output. Initially, council housing accounted for a substantial portion of new homes, but as policy focus shifted and funding decreased, so too did the output from this sector.

Additionally, the private sector, which could have compensated for the decline in public housing production, also faced numerous barriers. These included high costs of land, increased regulatory burdens, and the economic risk associated with large-scale development projects. These factors have consistently kept private sector house building rates below necessary levels to meet demand.

Moreover, economic and demographic shifts, such as increased urbanisation and changes in household compositions, have outpaced the supply of new housing. The combination of a restrictive planning system and the decline in both public and private housebuilding has resulted in a chronic undersupply of housing, exacerbated by the rising demand due to population growth and economic changes.

These historical and systemic issues point to the need for significant reforms, particularly in planning policies, to enable a major increase in housebuilding rates to address this long-standing issue.

Policy implications - Rent Controls

“Rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing” - Assar Lindbeck

In response to housing crises and high rents, it is common to seek police recourse. A populist intervention is to impose rent controls. This can be popular among the ill-informed, because it promises to limit rent rises. Economics teaches us this is profoundly misguided and only makes the root problem worse. So, while the Adam Smith Institute does not have a “house” position on policies, it has published repeatedly on the folly of rent controls.

Most recently, Sam Bailey wrote, Let’s explain again why rent controls are a bad idea for our blog. Other pieces include:

Rent controls have been tried, and have consistently produced bad results. Rent controls lead to a shortage of rental accommodation and a deterioration in its quality.

The reason why rent controls are so harmful is simple - rent controls mean landlords are forced to charge prices below the market rate. This fundamentally changes their incentives, meaning they invest elsewhere and some withdraw altogether. The supply of rental properties is even more constrained or falls. Quality is also reduced as landlords are forced to cut back or delay maintenance and renovation, because it is unprofitable. All the while, demand is unaffected or even boosted.

That is why ASI publications tend to focus on increasing the supply of homes, and focus on the incentive structures of those in the market. For a given amount of demand (and even more so with rising demand), an increase in supply is needed for prices to fall. Failing this, substantial productivity and wage growth is needed to make homes more affordable.

Policy implications - The role of landlords

Cost of Rent day is not intended as an attack upon Landlords.

Landlords often come under scrutiny in discussions about the housing market, yet their role is essential in ensuring the availability of quality, affordable housing. Economics tells us landlords are not just necessary but beneficial to a housing ecosystem.

Landlords invest substantial capital into the housing market, which is crucial for the maintenance and expansion of housing stock. By purchasing and upgrading properties, landlords not only enhance the quality of living environments but also absorb significant financial risks. These risks include potential vacancies, non-payment of rent, and fluctuations in property values. This deployment of capital and assumption of risk facilitate market functioning and contribute to the overall stability of the housing sector. They play a critical role in the efficient allocation of housing resources, assessing market demands and providing properties that align with consumer preferences and affordability.

Rental properties offer essential flexibility for a mobile workforce, particularly beneficial for individuals who need to relocate for employment without the burden of selling a home. This flexibility supports economic growth by enabling a more agile and responsive workforce. Professional landlords invest in the regular maintenance and management of their properties, which contributes to the overall desirability and safety of the living environment. Well-maintained properties also support higher property values and contribute to the aesthetic and practical appeal of communities.

Investments made by landlords also stimulate local economies. This includes employment for property management, construction workers, and maintenance staff, and increased business for local suppliers and service providers.

This defence does not extend to all landlords indiscriminately. Especially in the midst of a housing crisis, where competitive forces are diminished, there exist landlords who offer substandard properties that are poorly maintained, and others may even breach contractual agreements. These practices can exacerbate the difficulties faced by tenants, undermining the integrity of the housing market and furthering calls for aggressive intentions.

While it is crucial to address and even prevent practices that illegitimately disadvantage tenants, understanding and appreciating the role of landlords within a functioning housing market is equally important. By investing capital, managing risks, providing housing, and stimulating economic activities, landlords contribute significantly to the functioning and health of both local and national economies. By viewing landlords through this economic lens, we can appreciate their role not just as rent collectors but as essential contributors to the housing market's vitality and stability.

Policy implications - ASI ideas

The ASI has published extensive research on housing to help inform policy makers and academics. Highlights include:

YIMBY: How To End The Housing Crisis, Boost The Economy And Win More Votes

Children of When: Why housing is the solution to Britain's fertility crisis

Enhancing Cost of Rent Day analysis

The housing crisis extends beyond renters. It is too challenging to get on the housing ladder. The homes which people are able to buy are smaller, more remote, in worse condition, and more expensive than they should be.

The ASI is analysing the broader “Cost of Housing'' day, but data and modelling complications make this estimate much more challenging to produce in a simple and consumable way. Similarly, The ASI is also analysing the “Cost of Rent” day for the wider UK (not just England), and for missing local areas, however ONS data sources have inconsistencies and gaps that hinder the production of consumable estimates (produced with the same data sets, and using the same method). We have withheld this additional analysis from publication to avoid confusion. These issues are explored further in the methodology section below.

The ASI recommends that the ONS should start producing consistent statistics that:

Cover the whole UK, not just England

Avoid local area data gaps

Enable a better understanding of gross annual incomes, and how they are spent on taxation, housing, and key components (fuel and power, transport, food, recreation, hospitality, clothing, health, education etc.)

Focus on the quality and cost of housing to help inform policy makers

Notes on Cost of Rent Day and methodology

What is Cost of Rent Day?

Every the year, the Adam Smith Institute will calculate the number of days the ‘average’ renter (more on that later) would have to work to pay of their annual rent bill.

This year, every penny the average person earned until May 4th effectively went straight to their landlord. Only from May 5th onwards, Cost of Rent Day, does the average person get to spend their money on other things*.

We calculated Cost of Rent Day to illustrate the scale of the housing crisis in an intuitive way, and to track progress (or lack thereof) in addressing the root issue - a lack of housing supply, and stagnant wage growth.

*Unfortunately, this says nothing about taxation or the cost of Government - so actually the average person is even worse off! We have the longer running Tax Freedom Day and Cost of Government Day, for keeping an eye on that side of our economic malaise.

Calculation

To calculate the Cost of Rent Day monthly rents were converted into an annual figure. Then annual rents were divided by gross annual pay, to understand what proportion of earnings are spent on rent.

For example across England, if median monthly rent is £850, then that implies annual rent of £10,200. With a median gross annual pay or £29,919, that means 34% is spent on rent.

To balance for leap years and support better inter-year comparisons, a year is treated as being 365.25 days long.

Using otherwise unrounded inputs, this calculation implied 125 days of the year are spent on rent. The 126th day of the year is May 5th.

This is a deliberately simple calculation and as outlined above and below, will not capture the nuances of individual circumstances. However, it enables a simple, transparent, and intuitive calculation - this is preferable to more complex alternatives we developed.

Data Sources

To produce this analysis, the ASI used two readily available ONS data sources to readily enable reproduction and variants.

For rents, the “Private Rental Market Statistics” data was used. This provides median monthly rental prices for the private rental market in England by bedroom category, region and administrative area, calculated using data from the Valuation Office Agency and Office for National Statistics.

For earnings, the “Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE)” data was used, specifically, “Earnings and hours worked, place of residence by local authority: ASHE Table 8”. The provisional data for 2023 was used, and revised data for earlier years.

ASHE is based on a 1% sample of jobs taken from HM Revenue and Customs' Pay As You Earn (PAYE) records. ASHE does not cover the self-employed or employees not paid during the reference period.

Areas

The two data sets have common Area Codes, enabling the analysis across the 309 local areas and 9 regions, both data sets have in common, and where there are values.

The Median was used by default for both data sets. When a series of numbers are arranged by order of magnitude the median represents the middle value. The median was chosen instead of the mean, because the data sets are skewed and have outliers.

As the ONS note in their guidance around ASHE:

We use the median because the distribution of earnings is skewed, with more people earning lower salaries than higher salaries. When using the mean to calculate the average of a skewed distribution, it is highly influenced by those values at the upper end of the distribution and thus may not be truly representative of the average earnings of a typical person. By taking the middle value of the data after sorting in ascending order, the median avoids this issue and is consequently considered a better indicator of “typical” average earnings.

However, for 31 local areas, the mean was used because no mean pay figure was provided. These areas were: Arun, Bassetlaw, Boston, Burnley, Chesterfield, Chichester, East Cambridgeshire, Fareham, Fenland Folkestone and Hythe, Gravesham, Greenwich, Guildford, Harrow, Hertsmere, Mid Suffolk, North East Derbyshire, Oldham, Sevenoaks, South Holland, Stratford-on-Avon, Tower Hamlets, Uttlesford, West Lindsey, West Oxfordshire, Winchester, Worcester, Halton UA, North East, Lincolnshire UA, Windsor and Maidenhead UA AND Wokingham. While this means these 31 cannot be compared on a like for like basis with the other areas, it was more important to provide an estimate of Cost of Rent Day than none at all.

Ten local areas lacked annual pay figures altogether in the data set, so a Cost of Rent Day was not calculated. These areas were: City of London, Lichfield, Mid Devon, Mole Valley, North Devon, North Norfolk, Richmond upon Thames, Rochford, Torridge, Isles of Scilly, North Devon, Torridge

Six local areas lacked annual rent figures in the data set, so a Cost of Rent Day was not calculated. These areas were: Cumberland UA, North Northamptonshire UA, North Yorkshire UA, Somerset UA, West Northamptonshire UA, Westmorland and Furness UA.

In some of these sixteen cases a manual comparison was possible (using a similar/overlapping area), but as they lacked a formal ONS area code match, the analysis erred on the side of caution.

Across both data sets, there is a 1 year lag time. The analysis for calculating 2024’s Cost of Rent day, is based on data from 2023. This is because we want to identify the day during the year in which it takes place, and celebrate its passing, not simply conduct reactive analysis.

Simplifications

This analysis does not adjust for the fact that the ONS data sources do not mirror a calendar year. For example, the rental data for year N is taken from between October N-2 and September N-1. So for 2024, our rental data was recorded between October 2022 and September 2023.

The analysis is based on the average rent, across all types of rental. The data is broken down by rental type, including a ‘room’, ‘studio’, ‘one bedroom’, ‘two bedrooms’, ‘three bedrooms’ and ‘four or more bedrooms’ properties but this is not used in the headline calculation.

Taxation

The ASI used annual gross pay (before fiscal deductions / taxes) to generate these calculations.

It would perhaps be more interesting to produce Cost of Rent Day based on disposable income. One way the Government can help people with housing costs is by taxing them less, leaving them with more disposable income. For example, such a measure would see an improvement in Cost of Rent day (all things being equal) if taxes were reduced.

Unfortunately, in producing this analysis we did not find a readily available disposable income data set that also provides the same granularity by local area and region. Understanding disparities by local and area and region was considered more important than basing the Cost of Rent Day on disposable income only.

Comparisons - sample size limitations

The sample size used for the ONS rental data is limited meaning we cannot compare the data effectively across time periods or between areas.

As a result, the local area Cost of Rent days should be taken as indicative, and one should not read too much into differences.

Intent

As the complexities detailed above suggest, Cost of Rent Day does not correspond exactly to any individual’s experience. And yet many people do find it shocking to see how high rents are, expressed in an intuitive way.

Suggestions

Given the limitations outlined above, the ASI would welcome suggestions to enhance our analysis next year, including better data sets to use.

About the authors

James Lawson is Chairman of the Adam Smith Institute. He led on the creation of Cost of Rent Day.

Sarah Gall is an experienced data consultant, focusing on data analysis and visualisation. Sarah created the interactive tools using d3.js and provides data strategy and analysis services through Sarah C Gall Ltd.