As we've been known to say before, let's stop government doing some things

As our friends over at the IEA point out, close regulation and control might not in fact be the best way of managing matters:

Four in five sets of UK traffic lights should be torn down to reduce travel delays and boost the economy, a leading think-tank has claimed. The proliferation of traffic lights, speed bumps and bus lanes seen in Britain in recent decades is “damaging to the economy”, the report from the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) finds. It estimates that a two-minute delay to every car journey ends up costing the UK economy about £16 billion every year. “Not only is a majority of traffic regulation damaging to the economy, it also has a detrimental effect on road safety and the environment,” the report claims.

The full report is here.

There have been a number of empirical proofs of this contention. Traffic flowed better when a notorious set of lights in Beverly failed, a Dutch town has seen better traffic flow since mostly abandoning any detailed control. So, in the specific sense of traffic management, in certain conditions (we would not go so far as to say all) it is better to set general rules and then leave it to individuals to navigate their environment than it is to try and set detailed prescriptions for how each must act. Keep left, yield when necessary, be alert to what others are doing: rather than this file may move forward now, that in 30 seconds and so on.

What interests us is that this does, we are certain, apply in a more macro sense too. Yes, certainly, the economy as a whole needs certain basic rules. Don't cheat, play fair, do the best you can perhaps, but what it doesn't need is detailed rules. Bakers may only start to bake at 4 am, only shops at train stations may open on a Sunday, only those with a two year apprenticeship may drive a taxi in London, only a licenced electrician may change a kitchen plug.

The analogy is pretty direct really: leaving adults to navigate their local environment dependent upon the local conditions leads to smoother flow. Leaving most people, most of the time, to their own devices in navigating the economy leads to a better flow through said economy. And, of course, flow here is what we mean by economic growth: that's what it is to a great extent.

This is not to argue for no regulation: it's to argue for the necessary minimum to produce the flow. Traffic will not flow smoothly if people start to drive on the right in the UK (as the joke has it, odd plates the day before even). The economy will not flow, will not grow, if we do not have rules about what is whose and how exchange takes place and is acknowledged. But once the general rules are set then leave people to it. It is, perhaps, to argue for the common law approach to regulation: anything we've not said you may not do you can. Rather than the Roman Law approach, and yes we know this is over egging the difference a little, which is that only those things we've said you may do may be done.

An analogy rather than a hard and fast comparison, but the underlying point the analogy is noting is that local conditions are much too complex, to changeable, for any centre to be able to provide prescriptive rules for all circumstances for both traffic and the general economy. Thus we should concentrate on producing the decision making rules, simple ones, by which people can navigate those local conditions.

If you prefer, if it turns out that just us normal folk can guide a tonne or two of metal capable of 70 miles an hour and up through the complexities of life better than the bureaucrats can tell us how to do it then we're entirely capable of sorting out our desired toothpaste, sugar consumption, booze quantity, weight, exchange and style of living without their intervention.

Which leads us to something we say quite a lot around here. It's amazing how much better things can get if we just stop government doing some of the damn fool things it already does.

A Triumph in Disguise

TfL’s announcement of a fresh set of restrictive proposals for Uber is undoubtedly a victory for those of us who wish to avoid deliberate impediments to progress. The initial, much harsher, suggestions have been avoided. However, it will regardless be met by the right with reminders of the fantastic silliness of arbitrary regulation. And so it should, really. Amongst other things, the proposals require Uber drivers to: pass an English test; pass a geography test; and provide personal details to customers before the start of the journey. Fairly obviously, these are all trivial – their only justification could be that they somehow protect the customer from being cheated out of a proper service.

But no – were this the case, black cabs would surely come under the same restrictions. (Of course, they do all have to pass The Knowledge but this is decidedly self-imposed). The new proposals are aimed purely at reducing the productive potential of Uber, to the end of preserving the black cab tradition.

After all, if customers decided that whatever language barrier existed between them and their Uber driver was overtly disagreeable, they’d simply have never decided to transfer their custom between the cab services. A geography test would only ever be useful if it afforded such depth of knowledge that drivers could override what few errors their GPS systems make - 'Knowledge Lite' will do no such thing. Personal details tend to be of no consequence to the average consumer, as long as they’ve the assurance of Uber’s vetting process.

But we’ve heard this all before. What’s more important to take from this all is that the anti-Uber squad has backed down, and those of us who hope for a world in which inefficiencies are swiftly uprooted should enjoy the triumph.

This is a rum one from Corbyn

Well, perhaps not all that strange, given what little we think Jeremy Corbyn knows about business and economics. He's decided that companies should not be allowed to pay dividends to shareholders unless all staff are making the living wage. This fails on two counts: on the detailed knowledge of how the business world works and upon the underlying economics of wages works.

Here's the ramblings:

Companies should be banned from paying their shareholders dividends unless their staff earn the living wage, Jeremy Corbyn has said.

The Labour leader wants to ban chief executives from handing financial returns back to investors if they rely on “cheap labour” for their profits.

Well, partnerships don't pay dividends: thus partnerships, and there's a lot more of them out there than most people think, won't be covered while that small portion of limited companies that do are. It's simply not sensible to divide the economy in this manner.

But it's the misunderstanding of the economics that's so painful. For of course this will lower the amount of capital that is put into British business. But more capital going into British business is what raises wages. Good grief, even Marx got this right, it's the capitalists competing for the services of the workers that raises the price of labour. Thus we want more capital coming in, not less.

Corbyn's proposal will, over time, lower UK wages. And the tragedy is that he simply doesn't understand this, nor does his coterie.

We always said this was a mad idea and almost certainly illegal

We've been saying ever since the idea first came up that minimum pricing on alcohol was a thoroughly silly idea and one that was almost certainly illegal to boot. Yet there were people who just insisted that it just must be introduced. That second, that it's illegal, has been confirmed:

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has ruled that the Scottish Government’s plan for a minimum alcohol price would breach EU law if less restrictive tax measures could be introduced. Judges at the Luxembourg court concluded that the policy would restrict the market, which could be avoided by the introduction of an alternative tax measure designed to increase the price of alcohol.

We do get the basic contention of the puritan prodnoses behind this. If something is more expensive then people will presumably consume less of it. Yes, demand curves do slope downwards. But why on Earth you'd do this via minimum prices, rather than simply a generally higher excise duty on alcohol is something that's never been explained in any satisfactory manner. Because all you do with a mandated minimum price is fatten the profit margins of the people who make the cheap grot. And since when has that ever been a valid goal of public policy?

We're not, around here, and this writer especially, great fans of the European Union. But woe for national politics is that's the last defence against this sort of foolishness.

The case against Minimum Alcohol Pricing

The EU seems to have killed Minimum Alcohol Pricing, for now at least. That's good news, but the case against it will still need to be made as its advocates push for it despite its illegality. Last week I went on Ireland's flagship news programme, Prime Time, to argue against it. In Ireland, the price floor being proposed is €1 per 10g of alcohol, which is 12.7ml – so a can of beer with 20g of alcohol must be sold for at least €2.00, a 14% ABV bottle of wine with 85g of alcohol for at least €8.50, and so on. Drinks that are already priced above this floor will be unaffected.

Minimum Alcohol Pricing does not even succeed on its own terms, for two reasons. One, it is extremely regressive. And two, it will probably not affect problem drinkers as much as moderate drinkers.

- Minimum alcohol pricing is regressive.

Galahad lager is Aldi’s own brand beer here in Ireland, and you can buy normally buy twelve cans of it for €9 – 75¢ per can. It contains 16g of alcohol per 500ml can, so its price floor under Minimum Pricing would have to rise to €1.60 per can. A man and a woman who drink within the recommended amounts (which are very low – more than three pints in a day is defined as being ‘binge drinking’) can drink 170g and 110g of alcohol respectively, 280g in total, per week. This equivalent to 17.5 cans between two people per week – just over one can a day each. Almost everybody would agree that these are moderate drinkers.

At the moment, they can do this for €13.13 per week (if they buy a couple of weeks’ worth at a time). Under Minimum Alcohol Pricing, this rises to €28.00 per week, a difference of €14.87. Over the course of a year this means that a couple who drink within the very low recommended limit at home would be €773.24 worse off under Minimum Pricing.

When I put this to Dr Steven Stewart, an advocate of Minimum Pricing, on Prime Time he said this was “just wrong” and the true figure was 70¢ per week (€36.40 per year) per person. That might be true of someone who drinks a quarter of a bottle of wine a week, or for someone who buys more expensive brand name beer, but it is not true for people who shop at Aldi or buy other budget lagers and wines.

The impact of Minimum Pricing is not felt disproportionately by people on tight budgets, it is felt exclusively by them. Not only is this regressive, it is misplaced – alcohol consumption rises with income, as does drinking large quantities of alcohol. So we’re hammering the poor even though the poor don’t actually seem to be the problem.

- Minimum alcohol pricing doesn’t deter problem drinking, and the health benefits are overblown.

As we demonstrated in our 2012 report by former NHS statistician and epidemiologist John Duffy, “The minimal evidence for minimum pricing”, the model that Minimum Pricing advocates use is deeply flawed. Among the assumptions it relies on is that alcoholics and other problem users are more sensitive to price than moderate drinkers. That is, when the price of booze goes up, alcoholics are more likely to drink less than people who don’t drink very much.

This assumption is based on a misinterpretation of data. When the price of one brand of alcohol goes up, alcoholics are the most likely to switch to another brand – they are indeed price sensitive in regard to the type of alcohol they drink. But they are actually the least likely to reduce their consumption of alcohol in general – as meta-analyses of the evidence have shown. For the heaviest drinkers, price elasticity of demand is “not significantly different from zero” – they won’t drink less almost no matter how high the price goes.

Advocates of Minimum Pricing typically point to Canada’s success in reducing deaths from alcohol abuse after introducing minimum pricing. But the studies that show this are typically quite bad – most lack any control group which is essential in a situation where alcohol consumption has been falling anyway, almost across the Western world. Apart from this, the research is dubious:

The key finding was that over the period 2002–2009, “a 10% increase in minimum price for all alcoholic beverages was associated with a 31.72% reduction in wholly alcohol attributable deaths”. Whilst this study was greeted as a breakthrough by public health lobbyists, independent statisticians have demurred.

In fact, the actual finding was that a 1% increase in pricing gives an estimated 3.172% decrease in wholly alcohol attributable deaths. Despite the complex statistical analysis used elsewhere in the paper, the authors then used a simple multiplication factor to estimate that a 10% increase in prices would therefore give a 31.72% decrease in mortality rates. Even this lawyer can see that a simple linear relationship cannot hold true. If it did, a 33% increase in price would reduce the estimated level of deaths by over 100%!

Got that? They found that a 1% rise in the minimum price led to a 3% fall in deaths and then just multiplied that by ten. This is sloppy in the extreme, obviously wrong to anyone with even a basic understanding of the issue, and advocates of Minimum Pricing should treat it and the researchers who produced it with caution.

Other points

There are other points to be made against Minimum Alcohol Pricing. It is not justifiable on cost grounds – unlike excise duties, it does not raise any more money for the government, only for supermarkets. Ireland has the second highest alcohol taxes in the EU already and, morbid as it may be, because heavy drinkers die young they usually end up saving the state money on other healthcare, social care and pensions costs.

We don’t really need to do more to curb drinking, despite what doctors like to tell us. Under-age drinking has fallen by 25 percent in the last ten years, and alcohol consumption across the board has been falling for decades.

The Irish health minister, Leo Varadkar, likes to point out that Ireland consumes much more alcohol than the OECD average. But the OECD average is skewed because it includes large countries where large sections of the population barely drink at all, like Turkey, Japan and the United States (where a third of adults don’t drink alcohol at all). In fact, Ireland is behind Austria and France and just barely ahead of Germany in terms of alcohol consumption – countries not exactly known for their sobriety, but not problem cases either.

People drink alcohol because they enjoy it. Being drunk can be fun, and having a beer or a glass of wine after work can help us unwind and relax. Everybody knows this, yet the debate that is taking place seems to ignore this fact altogether.

Doctors advocating this should back off – they are here to give us advice about how to live healthily, not force healthy lives upon us through the law.

But you don’t need to be a liberal to oppose Minimum Pricing – the case in favour of it is paper-thin even on its own terms. It will not affect problem drinkers, but it will give a kicking to any moderate drinker living on a tight budget. For once, thank goodness for the EU.

Among the things this capitalist free market thing can deal with

We admit it, guilty as charged. Among the things we have never considered is the pernicious effect upon the malleable minds of young children of Lego not having any disabled figurines in their range. Fortunately, in this capitalist and free market world we live in, one that allows that division and specialisation of labour that Adam Smith so lauded, others have:

But the brand continues to exclude 150 million disabled children worldwide by failing to positively represent them in its products.

We'd say that's a rather strong statement of whatever problem there might be but this is the opinion of another and opinions, well, as with fundaments, everyones' got one. Apparently there's a reasonable number of people who feel the same way:

In response to a 19,000-strong change.org petition calling on Lego to act, Lego said: “The beauty of the Lego system is that children may choose how to use the pieces we offer to build their own stories.”

So, they can rally 19,000 people to their cause. Excellent: so why is it that change has not already happened?

The practicalities of capitalist market forces, the need to make a profit, perhaps determine this exclusion.

Ah, yes, capitalism, possibly even neoliberal sophistry, must be causing this. So, why is it that this mixture of capitalism and free marketry that we have not offer a route to solve such problems? The answer being that it does. For as the article concludes:

Vote for the #ToyLikeMe Wheelchair Santa on Lego Ideas. If it receives 10,000 votes Lego will consider it for production.

That capitalist and free market competing organisation, Lego, actually has a system set up to aid people in advising the company of the products they would like to see being made.

But, of course, the blame needs to be laid at capitalism's feet, as the article does indeed do. At which point I think we might argue that this is Peak Guardian. No, not because of the actual subject matter itself, although whining about what toys aren't being made does seem a pretty strange occupation for an adult. Rather that blame being laid upon capitalism: when firstly, capitalism provides exactly the communications channel they desire and secondly, the only reason it hasn't worked as yet is because those protestors have been sending their letters to the wrong place. To change.whatever it is instead of to Lego.

We really cannot see that an inability to select the correct address is a problem of capitalism, neoliberal or not. And it's most definitely something even more blitheringly stupid that any of Polly's output. Thus, Peak Guardian.

Or at least we can hope so. Otherwise we fear something like division by zero, or searching for Google in Google, the universe collapsing down to a point under the weight of the accumulated idiocy.

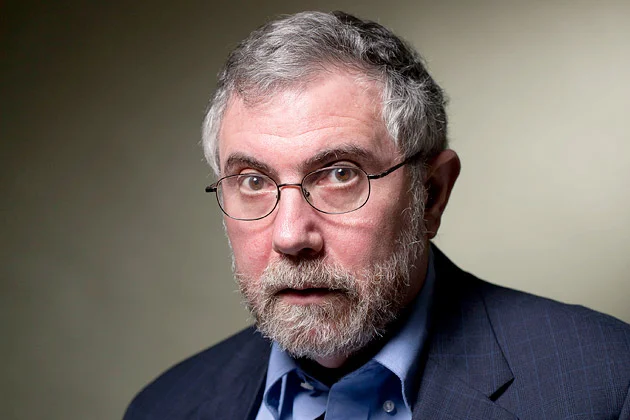

If you don't believe us will you believe Paul Krugman?

We've been repeating ourselves recently in shouting that the entire house price nonsense is simply a result of the restrictions on who may build what and where. The answer being to loosen or abolish those restrictions and the problems will go away. We have also been told that we're just thinking too simplistically. So, instead, how about President Obama's Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers and the Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman?

And this is part of a broader national story. As Jason Furman, the chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, recently pointed out, national housing prices have risen much faster than construction costs since the 1990s, and land-use restrictions are the most likely culprit. Yes, this is an issue on which you don’t have to be a conservative to believe that we have too much regulation.

Here in the UK housing prices have been rising much faster than building costs. We've got the same problem with the same cause: land-use restrictions.

The answer is, as we've been saying and as is said there, relax or abolish those land-use restrictions.

Abolish the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors.

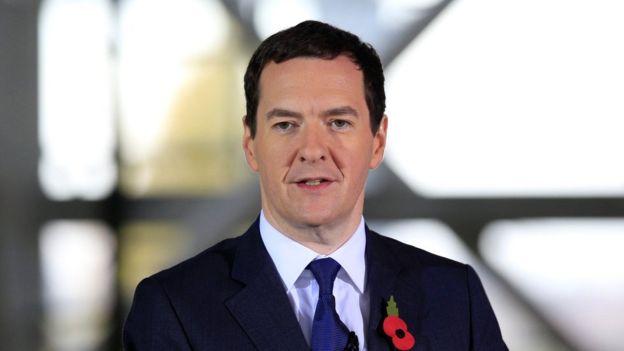

Why Osborne should be applauded for his business rate devolution proposal

One of the biggest surprise announcements from today’s Autumn Statement – aside from the Chancellor’s spectacular U-turn on tax credits – was the decision to hand local councils full control of business rates. But it was a welcome one, too: devolving rates should deter excessive spending and stimulate competition between councils, while encouraging local government to be more responsive to business needs. When the Chancellor first mentioned devolution during his Conference speech in October, over 60 per cent of IoD members came out in favour of the policy. The devil is in the detail of course, but at face value it’s hard to see a downside to the policy. Some have pointed to the potential for geographic disparities, but those rural communities likely to have the smallest rates receipts are predominantly run by fiscally responsible Tory councils.

Others suggest that local mayors will succumb to the temptation to hike rates (currently, the uniform business rate is set at 49.3 per cent of a non-domestic property’s free-market rental in England and 48.2 per cent in Wales) to raise revenues without the consent of the local landowners. The assumption – or hope – is that accountability to their local electorate will help them resist.

But while business rates have long been criticised by businesses (and any cut welcomed), it is important to note that it’s not occupiers that end up shouldering the financial burden but landowners. So the notion than business rates cuts, as a result of devolution, could bring business into an area is a misconception: business rates cuts lead to rent rises in almost exact proportion.

And business leaders will need to be better engaged with local government to ensure councils are fiscally responsible. For example, city-wide mayors will be given the power to levy a business rates premium for local infrastructure projects, and as such businesses will need to make sure their views are properly voiced through their Local Enterprise Partnership.

From now on, it looks like businesses are going to get the local government they deserve.

Sorry Jezza, steel plants and banks aren't alike at all

It would appear that Jeremy Corbyn does not realise that one thing is not like another thing: that banks and steel works are not the same.

In a speech to Labour’s Eastern regional conference in Stevenage, Corbyn will say that the prime minister should follow the interventionist route of Gordon Brown during the banking crisis and step in to help workers. “We need Cameron and Osborne to act as decisively in 2015 as Gordon Brown did in 2008, when Labour part-nationalised RBS and Lloyds to prevent economic collapse,” Corbyn will say.

“If the Italian government can take a public stake to maintain their steel industry, so can we. That’s why Labour will be pressing Cameron to use the powers we have to intervene and, if necessary, take a strategic stake in steel – to save jobs and restructure the industry.”

Bailing out the banking system was the right thing to do, bailing out the steel industry would not be. This is not because bankers tend to come from the same background we do while steel workers are northern working class types. Rather, it's essential that a modern economy have a financial system and it's not essential that a modern economy have a domestic blast furnace or two. For it's actually impossible to have anything at all resembling a modern economy without a financial system. But as long as someone, somewhere, has a few blast furnaces then we'll be just fine, we don't actually have to have any, any more than we need to grow our own bananas, coffee or Bourdeaux domestically.

We're not entirely fans of the way that banking was bailed out, that's true enough: rather more shareholders and even banking management might have been led to the chopping block to satisfy our tastes. But that we need to have the system itself is obvious.

There is a further issue as well: imagine that there was indeed a part nationalisation leading to a restructuring of the industry. The outcome of this would be that the very same plants which are now closing would close. Simply because it is still true that a modern economy doesn't need to have so many blast furnaces hanging around. Just as one technical example, the Redcar plant imported all of its raw materials (the original location was because all could be locally resourced but that's long gone). There's little to no economic point in importing such raw materials to transform when we lose money by doing so. Especially as we can have that transformation done for us elsewhere and just import the steel.

Thus nationalisation would, if done properly, change the outcome not one whit. And if it doesn't change the outcome not one whit then the nationalisation wouldn't be being done properly. So, let's save all our money and not do the nationalisation then.

To understand why economic growth is slow look at Keystone XL

The saga over Keystone XL is an excellent example of why rich world economies are in general slow growing at present.

President Barack Obama rejected the Keystone XL oil pipeline on Friday, in a move that infuriated conservatives but will bolster his legacy on environmental issues ahead of next month's climate change summit in Paris.

No, not because the pipeline will now not be built, not because of those climate negotiations and no, not because conservatives are unhappy about this.

The pipeline was to bring Canadian tar sands oil down to the refineries on the Gulf Coast. Very simply, refineries further north just aren't set up to process such heavy crude. The ones on the Gulf are. So, instead of changing all the refineries, build the pipeline to get the oil to where it can be efficiently processed. And that's really it.

Given current crude prices those tar sands are shutting down some production and the whole plan is just less important than it was. And while the plan did indeed have a positive current net present value (and thus was something that made us all generally richer) it wasn't either as earth shattering as the proposers suggested nor as earth shattering as the environmental protestors insisted. And in something the size of the US economy something like an oil pipeline or not is always going to be a marginal decision.

The decision whether to build it or not is obviously highly interesting for those directly involved and for the rest of us very much a "Meh" question. Except for this:

Mr Obama's announcement follows a seven-year review process

It's worth noting that it is only phase IV of the project that has been cancelled. The other three phases are up and running. And they each took between one and two years to build.

That is, we now have a system whereby it can take 7 years to get a decision on whether one can build something which takes two years maximum to build. And that is why modern economies have a slower growth rate than they perhaps should have. Not because people aren't allowed to do things like build oil pipelines, but because the entire economy is being strangled by red tape.

Perhaps we should have environmental regulation of the type that stops such building. Perhaps we shouldn't: the existence or not of such regulation isn't the problem at hand. What is the problem is that whatever the decision is it needs to be made quickly. So that either the project can be built or, if rejected, then everyone can stop their efforts at filling out paperwork and go off and do something more interesting.

We obviously do have our view of which way this decision should have gone. But that isn't our point today. Rather, if we're going to have a system of regulation over who may do what then it has to be an efficient system of deciding who may do what, how and when. Even to whom. Otherwise the entire economy will descend into a welter of form filling that would make C. Northcote Parkinson proud and the rest of us poorer than we need be.