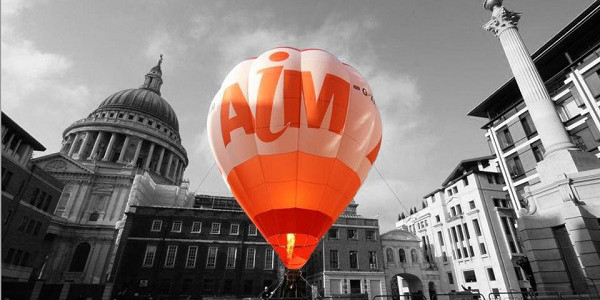

Asos Asos, the online fashion retailer, is one of the most famous success stories since Aim’s debut in 1995. Asos was initially priced at 3p and share prices once soared as high as £70 (now close to £38, after a major swing in value). Since the beginning of the year, shares have risen by 49 per cent.

Fevertree Drinks In 2005, Charles Rolls and Tim Warrillow joined forces to change the face of tonic water, finding an alternative preserver to sodium benzoate and instead using high quality quinine. A newbie to Aim, share prices have soared 65.51 per cent in the past six months. Today, the company sells more than 60m bottles of its premium mixers in 50 markets.

Fitbug Fitbug tracks sleep, steps, and estimates calories burned, and was founded in 2005 by ex-management consultant Paul Landau. At around £40, the Fitbug Orb device affordable compared to its competitors and it is now stocked by major retailers. Its share price soared late last year, and despite a correction this January, is still up 675 per cent in the past 52 weeks.

GW Pharmaceuticals One of Aim’s great success stories, GW Pharmaceuticals – the biopharmaceutical company founded in 1998 and best known for its MS treatment product Sativex – is listed on both the Nasdaq Global Market and Aim. In the past five years, share prices have rocketed from just over a pound, to 655p today.

Majestic Wine A favourite tipple of investors in the Aim for years, Majestic Vintners opened its first wine warehouse in Wood Green in 1980. In 1996, the company floated and it now has 200 stores and an online platform. Despite a rocky 2014, Majestic’s share price has risen 4.67 per cent in the past year.

Portmeirion You may be surprised to learn that a company specialising in tableware has become one of the most successful in the UK today. Over 40 per cent of its sales are to the North American market, and the company sells almost as much to South Korea as it does to the UK. Portmeirion has never cut its dividend and has been paying out since 1982.

Nevertheless, the market has been plagued by poor returns and a host of corporate failures – including some high profile fraud cases (the Langbar International fraud was once branded “the greatest stock market heist of all time”). And let us not forget that the market has performed pretty poorly over the years, with annualised total returns of -1.6 per cent per year when measured over the past two decades.

Nonetheless, Aim shares have surged in popularity since 2013, when they became eligible for inclusion in Isas. The high-risk factor had previously stopped the government from removing the restriction, but a desire to ensure that small and medium-sized companies – which are driving the economic recovery – have sufficient access to funding led to it reversing this decision.

It was the right choice: without Aim, there was a risk these companies would have turned to Nasdaq, or simply failed to grow. Research from Grant Thornton has also revealed that the companies listed on Aim paid £2.3bn in taxes in 2013 and directly employed 430,000 people at the end of that year.

For investors, Aim shares remain one of the most tax-advantaged options. If held through an Isa, benefits include no capital gains tax (CGT), no tax on dividend income, and no stamp duty. In addition, once certain Aim shares have been held in an Isa for a two-year period, they can qualify for Business Property Relief (BPR) and thus up to 100 per cent exemption from inheritance tax (IHT).

But the market is volatile: in 2008, for example, it lost around two-thirds of its value. Neither does the market offer plain sailing for the smaller companies that choose to list on it. Analysts predict that floating on Aim can cost anywhere between £400,000 and £1m – so for businesses with a projected market capitalisation of less than £25m, it may not be worth considering. 2014 research from accountancy firm UHY Hacker Young found that professional fees paid by companies to brokers and nominated advisers for a placing on aim accounted for 9.5 per cent of all funds raised.

And many of the mining, oil and gas companies (which account for a whopping 40 per cent of the market) that listed on Aim have since gone bust – among them ScotOil, African Minerals and Independent Energy Holdings. Firms involved in exploration for natural resources are among the riskiest of all: if a company digs for oil and there’s none to be found, the money raised for exploration has all but gone down the drain.

But should the government be doing more to serve the needs of smaller companies? Xavier Rolet, chief executive of the London Stock Exchange, certainly thinks so. Compared to the US, there are relatively few UK companies that progress to mid-size (and then on to become multibillion pound corporations like Facebook or Google). And as Rolet recently told the CBI:

“The entire business and financial community is working to nurture and celebrate these firms. But we must continue to challenge the status quo and not become complacent. We need to carry on fostering, through policy and practice, a richer, more diverse entrepreneurial ecosystem, so that the UK’s high-growth firms can take root and flourish.”

Rolet is right. Although floating your company isn’t the only way to grow a business, it needs to remain a workable option: particularly if we are to get the share-owning democracy that so many in the current government crave.

This article was first published by The Entrepreneurs Network.