We shouldn't have to care who has political power

An extremely good point made by Scott Sumner:

I consider myself to be reasonably well informed. I generally know which party is in power in countries like Sweden. And yet at no time in my life could I name a single Swiss political party, or political figure. There's a lesson there somewhere. Perhaps the lesson is that you don't want to live in a country where it matters a lot who gets elected President.

Our knowledge of Swiss politics is similarly deficient. We're not even sure if they have a party political system. Yet it does have to be said that the country runs pretty well. So perhaps the agonising that we have to do over who does gain political power here is what the problem actually is. Our recent ability to chose between a scion of the haute bourgeoisie and a man intellectually bested by a bacon sandwich may not have been the most edifying spectacle, but the problem is that we had to worry about it at all.

The point about politics is to come up with some method of getting the bins taken out. And that's a reasonably simple task and one that the Swiss most definitely have a handle upon. It's also necessary to have someone called "the government" simply because visiting dignitaries expect there to be one. But over and above that the place that seems to be governed best is the one where pretty much no one pays any attention to who is governing simply because it's not very important who is. Because politics simply doesn't intrude much into anyones' life.

We recommend it as a system. Anything important can be decided by the people in referenda, there's a bit of bureaucracy necessary and then let people just get one with things as they wish. Something of a plan, eh?

George Osborne's political economy

A blanket ban on psychoactive substances makes UK drugs policy even worse

It is a truth under-acknowledged that a drug user denied possession of their poison is in want of an alternative. The current 'explosion' in varied and easily-accessible 'legal highs' (also know as 'new psychoactive substances') are a clear example of this.

In June 2008 33 tonnes of sassafras oil - a key ingredient in the production of MDMA - were seized in Cambodia; enough to produce an estimated 245 million ecstasy tablets. The following year real ecstasy pills 'almost vanished' from Britain's clubs. At the same time the purity of street cocaine had also been steadily falling, from over 60% in 2002 to 22% in 2009.

Enter mephedrone: a legal high with similar effects to MDMA but readily available and for less than a quarter of the price. As the quality of ecstasy plummeted (as shown by the blue line on this graph) and substituted with things like piperazines, (the orange line) mephedrone usage soared (purple line). The 2010 (self-selecting, online) Global Drug Survey found that 51% of regular clubbers had used mephedrone that year, and official figures from the 2010/11 British Crime Survey estimate that around 4.4% 16 to 24 year olds had tried it in the past year.

Similarly, law changes and clampdowns in India resulted in a UK ketamine drought, leading to dabblers (both knowingly and unknowingly) taking things like (the once legal, now Class B) methoxetamine. And indeed, the majority of legal highs on offer are 'synthetic cannabinoids' which claim to mimic the effect of cannabis. In all, it's fairly safe to claim that were recreational drugs like ecstasy, cannabis and cocaine not so stringently prohibited, these 'legal highs' (about which we know very little) probably wouldn't be knocking about.

Still, governments tend to be of the view that any use of drugs is simply objectively bad, so the above is rather a moot point. But what anxious states can do, of course, is ban new legal highs as they crop up. However, even this apparently obvious solution has a few problems— the first being that there seems to be a near-limitless supply of cheap, experimental compounds to bring to market. When mephedrone was made a Class B controlled substance in 2010, alternative legal highs such NRG-1 and 'Benzo Fury' started to appear. In fact, over 550 NPS have been controlled since 2009. Generally less is known about each concoction than the last, presenting potentially far greater health risks to users.

At the same time, restricting a drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 requires evidence of the harm they cause (not that harm levels always bear much relation to a drug's legality), demanding actual research as opposed to sensationalist headlines. Even though temporary class drug orders were introduced in 2011 to speed up the process, a full-out ban still requires study, time and resources. Many have claimed the battle with the chemists in China is one lawmakers are unlikely to win.

And so with all of this in mind, the Queen's Speech on Wednesday confirmed that Conservatives will take the next rational step in drug enforcement, namely, to simply ban ALL OF THE THINGS.

In order to automatically outlaw anything which can make people's heads go a bit funny, their proposed blanket ban (modelled on a similar Irish policy) will prohibit the trade of 'any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect', and will carry up to a 7-year prison sentence.

Somewhat ironically for a party so concerned with preserving the UK's legal identity it wants to replace the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights, this represents a break from centuries of British common law, under which we are free to do something unless the law expressly forbids it. This law enshrines the opposite. In fact, so heavy-handed and far-reaching is the definition of what it is prohibited to supply that special exemptions have to be granted for those everyday psychoactive drugs like caffeine, alcohol and tobacco. Whilst on first glance the ban might sound like sensible-enough tinkering at the edges of our already nonsensical drug policy, it really is rather sinister, setting a worrying precedent for the state to bestow upon citizens permission to behave in certain ways.

This law will probably (at least initially) wipe out the high street 'head shops' which the Daily Mail and Centre for Social Justice are so concerned about. However, banning something has never yet simply made a drug disappear. An expert panel commissioned by the government to investigate legal highs acknowledged that a 50% increase in seizures of Class B drugs between 2011/12 and 2013/14 was driven by the continued sale of mephedrone and other once-legal highs like it. Usage has fallen from pre-ban levels, but so has its purity whilst the street price has doubled. Perhaps the most damning evidence, however, comes from the Home Office's own report into different national drug control strategies, which failed to find “any obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country”.

The best that can be hoped for with this ridiculous plan is that with the banning of absolutely everything, dealers stick to pushing the tried and tested (and what seems to be safer) stuff. Sadly, this doesn't seem to be the case - mephedrone and and other legal and once-legal highs have been turning up in batches of drugs like MDMA and cocaine as adulterants, and even being passed off as the real things. Funnily enough, the best chance of new psychoactive substances disappearing from use comes from a resurgence of super-strong ecstasy, thanks to the discovery of a way to make MDMA using less heavily-controlled ingredients.

The ASI has pointed out so. many. times. that the best way to reduce the harms associated with drug use is to decriminalise, license and tax recreational drugs. Sadly, it doesn't look like the Conservatives will see sense in the course of this parliament. However, at least the mischievous can entertain themselves with the prospect that home-grown opiates could soon be on the horizon thanks to genetically modified wheat. And what a moral panic-cum-legislative nightmare that will be...

Well, yes and no Professor Krugman, yes and no

The economics of this is of course correct For Paul Krugman is indeed an extremely fine economist:

We may live in a market sea, but most of us live on pretty big command-and-control islands, some of them very big indeed. Some of us may spend our workdays like yeoman farmers or self-employed artisans, but most of us are living in the world of Dilbert.

And there are reasons for this situation: in many areas bureaucracy works better than laissez-faire. That’s not a political judgment, it’s the implicit conclusion of the profit-maximizing private sector. And people who try to carry their Ayn Rand fantasies into the real world soon get a rude awakening.

The political implications of this are less so, given that Paul Krugman the columnist is somewhat partisan.

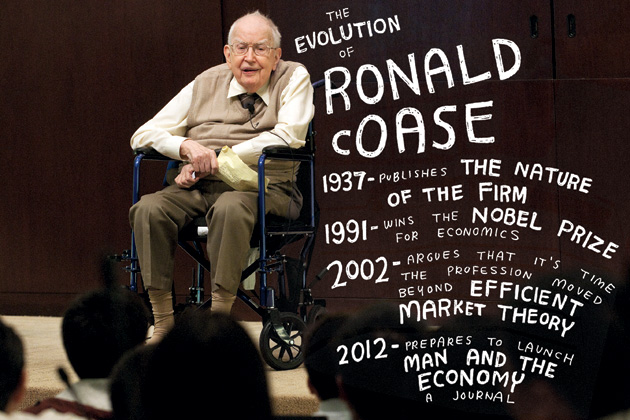

And of course that implication is that since that private sector (as Coase pointed out a long time ago) uses bureaucracy at times then we should all shut up and simply accept whatever it is that the government bureaucracy decides to shove our way.

Which is to slightly miss the point: yup there's command and control islands in that sea. Bit it's that sea that srots through those islands, sinking some and raising others up into mountains. Which is something that doesn't happen with the monopoly of government bureaucracy: they don't allow themselves to get wet in that salty ocean of competition.

That planning and bureaucracy can be the most efficient manner of doing something? Sure. That sometimes it's not? Sure, that's implicit, explicit even in the entire theory. How do we decide? Allow that competition. It's the monopoly of the government bureaucracy that's the problem, not that we somtimes require pencil pushers to push pencils.

A glorious example of political naivety

There's any number of lessons that we might take from the past few years. Fragile banking systems aren't a good idea perhaps. We seem to have shown that monetary policy is still effective at the zero lower bound, therefore fiscal policy isn't the only thing we can turn to in recession. The eurozone is giving a useful empirical lesson in optimal currency areas. There's all sorts of things we can and should learn from recent times. But then it's also possibly to be hoplessly naive about all of this:

The biggest surprise for me, and perhaps it shouldn't have been, is the degree to which politicians are willing to put political interests ahead of helping people in need. Watching the political/policy reaction to the Great Recession was both disappointing and eye opening.

Well, no, it shouldn't have been. Ourselves we waver between thinking that public choice theory is the right way to think of this (politicans and bureaucrats are subject to the same incentives of self-interest as everyone else) and the pronouncements of Mancur Olson (all governments are bandits exploiting the population and about the best we can hope for is a stationary bandit, not a roving one) dependent upon the crust of our liver on any particular day. But either insists that we cannot look to the political class as being interested in either what we want or what we need: not unless it's going to directly impact upon our propensity to vote for them so that they get to stay part of that political class.

The idea that a professional economist should believe that politicians would ever put helping people in need above political interests strikes us as simply hopelessy naive. However, this is still a good outcome: the next politician promising that we're going to run the world off kisses and unicorn parps is less likely to be believed now, eh?

An odd theory but it's ours and we like it

As a result of a conversation going on elsewhere an odd little theory but as it is ours we rather like it. So, why is it that foreign state owned companies are able to run things rather well in Britain (trains, water, electricity, whatever) while when the same companies were British state owned they were appalling? It's almost as if only the British state is appalling at running things. To which we would say yes: the British state is appalling at running commercial enterprises in Britain. As if the French state in France, the German in Germany and so on. There's a tad of hyperbole there but here's the reason why.

Politicians running something (the definition of course of the state running anything) are going to run it with an eye to politics. The art of getting elected is, of course, to build a large enough coalition to get elected. This does mean pandering to various constituencies: the workforce of that state run business, the unions, the capitalists (for a different flavoured coalition) and so on. That concern over getting elected rather outpaces the single minded focus upon efficiency (and if you're cynical about capitalism, that efficiency can be in extracting profit,) that the private sector at least strives to through competition.

It's not so much that know nothing politicians inevitably screw up whatever they do. It's that the incentives for a politician running something are different given that he's got both the organisation itself to think about and all of those electoral pressures.

But that same organisation, when freed from those political concerns, might be reasonably efficient at doing whatever. So, for example, French politicians don't give a rat's ar....well, no, this is a family blog, ...don't care one whit about the political heft of British unions. In a manner that British politicians very much do. The same is true on the other side of the political ledger. Which way the media plutocrats instruct the populace to vote doesn't matter a darn for a politician in a different media market, in a different language. And no one at all has won or lost a French election on the performance of the 7.15 from Brighton to Waterloo.

The end result of this, we admit slightly odd, argument is that the British state would be just fine running the French railways, as the French state owned companies seem not bad at running portions of the British ones. Simply because being outside the political jurisdiction that elects the politicians at the top the politicians don't have those conflicted incentives and can thus allow the companies simply to run as companies, not as political arms of the state.

Or as we might also put it: by being outside the political jurisdiction that owns them allows state companies to simply be competitive companies.

In which we find ourselves agreeing with Owen Jones

We found ourselves agreeing with George Monbiot earlier this week and now we find, to our surprise, that we're agreeing with Owen Jones. Must be something in the water:

Being “normal” often means having a complex life. A huge chunk of the population have taken drugs, cheated on a partner, slept with or gone out with someone they regret, been unfair to someone close to them or a stranger. Maybe we committed some misdemeanour when we were younger. Personally I would prefer more MPs with complex backstories, because that makes them more representative and more human. But with the promise – the threat – of unforgiving media intrusion into every last facet of our personal life, why do we expect normal people, with complex lives, to stand for elected office? And then we complain that our politicians are boring on-message robots.Chuka should have expected it and learned to take it, some will say. It’s all part of the territory. If you don’t want that level of intense scrutiny, choose a different path in life. You saw what they did to Ed Miliband, did you not? What a bleak approach, that the price of political service should be having your life and the lives of those who love you torn to shreds. A mean, cruel, macho, debased political “debate”, stripped of humanity or understanding.

Indeed. The corollary of which is that those who do glide into the higher levels of politics are drawn from the inhuman part of the population, those who never have actually had what the rest of us would consider to be life experience.

Meaning, of course, that we want them to have as little as possible to do with how the rest of us do live our real lives as they've obviously got no clue. Yes, we do need some method of working out who is going to collect the rubbish so there will always be a need both for politics and politicians. But given that, as Jones points out, it's only the nutters and sociopaths who are willing to go through the process of gaining that political power we obviously want that power limited only to those areas where it is absolutely essential.

Thus roll on the minimal, even minarchist, state. As Owen Jones will no doubt shortly agree.

How I learned to stop worrying and love electoral politics

ASI bloggers spent a decent wodge of time blogging about how democracy is silly or irrelevant or bad. I'm probably the worst here. But I have to say that I had a great time following the election, which was instantly hugely exciting and shocking and interesting after the truly unbelievable 10pm exit poll.

My experience has led me to perhaps a more sanguine view on this central institution of modern developed society.

Democracies don't make that much difference to policy—possibly because technocrats rule anyway. Democracies potentially lead to less violent transfers of power. Democracies may make people happy through recognising people's fundamental equality. Democracies may make people feel like they're having a say. And democracy is a fantastic spectator sport.

1. Democracies and non-democracies that are otherwise similar have quite similar policies, except that non-democracies may have more progressive tax schedules. (pdf)

2. It feels likely that democracies minimise the costs of power transitions. I'm not absolutely sure about this one, because I can't find any good papers (please send them my way). If you can vote people out, you don't need to fight them out.

The problem is that democracies tend to be systematically different to non-democracies in loads of ways (e.g. Western Educated Industrialised and Rich as well as Democratic). Just looking at how power changed hands in 1700s France and how it does now might not be enough. Ditto comparing France now with, say, Algeria.

And I can at least imagine transition mechanisms that would make monarchies even more flexible than democracies, if changing all the king's advisors counts as a transition as well as changing the man himself. But let's chalk this one down anyway.

3. When you drill down, lots of people value democracy for more than its supposed benefits for picking policy. People think that fundamental equality of humans/citizens is very important, and this is an important way of recognising it. If lots of people care about it then it probably makes them all a bit happier and more satisfied with their lives which is good. Obviously I'd need to see evidence to be sure, but again it seems an under-researched topic.

4. This is slightly different to the above. Voters are very unlikely to make a difference; it's about 10m to one in swing states in the USA; and the closest ever parliamentary election was decided by two votes, but then redone anyway for a gap of hundreds. No single vote ever makes a difference to the direct outcome.

But it's quite reasonable to view a vote as being 'a say', even if it's not necessarily heard in policy. And if this siphons off popular dissent and makes people identify more with their government and society it might make people more satisfied with their lives, which is good.

5. This is really how I changed during this election: it was so exciting. I didn't really go into the election caring about who won, except that I hoped the Lib Dems held up and UKIP didn't get too many seats—I didn't vote or even spoil like last time.

But as it turned out I got caught up in it all and had a great time cheering and booing. Think how many people are made happier by sports—and politics is like a sport which really matters in measurable ways!

I never really got het up about democracy, but I've decided I'm a whole lot more comfortable with the whole thing.

Why we vote the way we vote

In my last post I tried to understand why people vote, suggesting that even if a sense of civic duty or a desire to express oneself can explain why we turn out to vote, these can’t really tell us much about why we vote the way we vote. In this post I'll try to explain why I'm convinced that, for voters, ideas matter. There are two basic views among political scientists about this: people vote to maximise their own wellbeing (“pocketbook” voters) or people vote to maximise the wellbeing of their society (“sociotropic” voters). The literature here is enormous so this post will try to sketch out the argument broadly – it is not intended to be anywhere near comprehensive.

There is a clear correlation between declines in GDP per capita and declines in support for the political party in power ('economic voting'). But this could be because people who are worse off are changing their votes to improve their own welfare, or because people in general are trying to improve their society in general.

In ‘Sociotropic voting: The American case’, Donald Kinder and D. Roderick Kiewiet look at how voters behave when their personal circumstances differ from those of society in general – if you are unemployed, but total unemployment is low, are you more likely to want a change of government?

Looking at Congressional elections during the 1970s, they find strong evidence that people are more concerned with society and the economy as a whole than for their own circumstances.

‘A person’s private economic experience had very little impact on his choice of candidate in the congressional elections whereas his sociotropic judgements were of the utmost importance … American voters resemble the sociotropic ideal, responding to changes in general economic conditions.’

Kiewiet’s conclusion in a later book is that people blame factors other than the government for their own circumstances, but blame the government for the overall state of the economy. Is this a uniquely American phenomenon, though?

Leif Lewin’s review of the evidence in his excellent Self-interest and public interest in Western politics suggests that it is not – Western European voters, including British voters, also seem to be much more inclined to vote sociotropically than with regard to their own circumstances.

We know that voters are mostly very ignorant of the facts of politics, which may make it very hard for them to form accurate judgements about the best policies to achieve the end-goals they have in mind. But it also means that the media that they do pay attention to has an enormous influence over their perceptions, and that people’s political awareness may affect how ‘benevolent’ they really are.

In light of this, Gomez and Wilson (2001) adapt the pocketbook thesis to argue that more sophisticated, politically aware voters are more likely to be affected by pocketbook factors than others.

They are the ones who can think in terms of specific policies, make connections between particular policies and their own incomes, and do not blame incumbents for everything that goes wrong with the economy.

Other, less sophisticated voters simply assume that the President is responsible for what goes wrong with the economy. That might explain why electoral ‘giveaways’ (pensioner bonds, opposition to new home builds) seem to be concentrated on quite small groups of well-heeled voters – nobody else would notice.

The last word on voter behaviour must go to Philip Converse, whose 1956 survey data showed that most voters make their decisions based on extremely broad judgements of the ‘sign of the times’ (22%), or based on which group – posh people? workers? – a party or politician seems to speak for (45%), or even evaluations that had no shred of policy significance whatever, like which candidate was the funniest (17.5%).

Only around 15% of voters used ideology or ideology-like rules-of-thumb to decide who to vote for, and those were the most rigid in their decisions about how to vote.

To sum up, people seem to mostly vote for the candidates that they think will be best for society as a whole, though they may make very poorly considered judgements of that. If there is a ‘pocketbook’ effect, it is probably limited to the most well-informed voters.

All this suggests that the public choice view of democracy as just a way to divide the spoils of government between interest groups may well be wrong. Yes, voters are amazingly ignorant of basic facts, let alone economic theory, but we do have a chance of persuading them and changing the world for the better. To those of us who would like to believe in the power of ideas, that’s something to celebrate.

America's only socialist opposes Americans trading with socialists

Bernie Sanders running for President was always going to provide some amusement. But we didn't think it was going to come quite so soon after America's only declared socialist in Congress made his announcement. Sanders is against eh idea that America should sign the trade deals that Obama is urging that America does. And as Tyler Cowen has pointed out the country most likely to benefit from said trade deals is the at least nominally (and very poor, there's a connection there) socialist country of Vietnam. It's thus possible to note that:

Note his position the the US needs to “fundamentally change our trade policies, so that corporations don’t shut down in this country and move to China or Vietnam or other low-wage countries.”

Yes, the socialist candidate for US president is talking about keeping American jobs from migrating to the “socialist” countries of China and Vietnam.

Politics: it's a rum manner of trying to run the world, isn't it?

We would also like to note that this blog post was created on International Workers Day, May 1.