Someone's got a very dark sense of humour concerning Cuba

Much chuntering about the fact that Broadway musicals have returned to Cuba for the first time in 50 years. And whoever it was that put this package together they've a very, very, dark sense of humour:

In the play, the setting is New York: the East Village, in the early 1990s, with a bohemian, artistic crowd trying to make ends meet over Christmas.In real life, the setting is Havana – with a disparate group of actors, trying to put on a musical, to show over the festive period.

Because for the first time in 50 years, a Broadway musical is transferring to the Communist island, and – in a case of life imitating art – a play whose first scene opens on Christmas Eve will raise its curtain on December 24. Rent will then open to entertain crowds of curious Cubans, most of whom will never in their lives have seen a musical on that scale.

"Getting permission to bring the show here was extremely challenging," said Robert Nederlander Jr – producer of the show, and the third generation of a Broadway dynasty. "It took us well over a year to negotiate."

Our best guess is that we should congratulate Mr. Nederlander on that sense of humour.

Rent is a story (loosely a story, a collection of songs loosely nailed to a story might be a better description) detailing the travails of various people of interesting sexuality, their struggles with being HIV positive, the threats of becoming so, and how they cannot find secure and decent housing.

To take this to an island that, until recently, would lock up in isolation camps those who were HIV positive, distinctly demonise those of interesting sexuality and where there hasn't been decent or secure housing since the socialist revolution is, well, it is humorous, isn't it?

Well done Mr. Nederlander, well done, our caps are raised in admiration. We are left wondering though who, other than you and ourselves, is going to get the joke.

Europe’s Digital Dirigisme

Google has recently announced that it is ending its Google News service in Spain before a new intellectual property law – dubbed the ‘Google tax’ – requires Spanish publishers to charge the company for displaying snippets of their articles. Whist newspapers claim that Google infringes copyright by using their text, Google argues that their News service drives traffic to the featured websites, boosting advertising revenues. Certainly, Germany’s biggest publisher Axel Springer scrapped plans to block Google from their news items when they discovered that doing so caused their traffic to plunge.

This is yet another complication of Google - EU relations. In May, the European Court of Justice ruled in favour of the ‘right to be forgotten’, which has so far resulted in over 250,000 takedown requests. Building on this 'success', the EU now wants to force search engines to scrub ‘irrelevant or incorrect’ (read: inconvenient) links at a not just a European but a global level.

And as the European Commission’s four-year antitrust investigation into Google drags on, the European Parliament symbolically voted to break up its operation and ‘unbundle’ its search function from other services. Whilst the parliament has no power to touch the internet giant, it sends a very strong message as to what European politicians want.

European politicians portray such moves as guarding against monopoly, enabling fair competition and safeguarding the privacy of individuals. However, it’s not obvious that the way Google presents search results is to the detriment of its actual users (as opposed to rival firms), whilst the ‘right to be forgotten’ sets a dangerous precedent against internet openness. American firms and politicians have responded harshly to the actions, branding them politically motivated, anti-competitive and detrimental to trade relations.

European policy makers should be very careful not to cause harm to the digital economy through politicized regulation. Policymakers may be concerned by the digital domination of American firms like Amazon, Facebook and Google – yet it's worth noting Europe fails to produce many rivals of its own.

As the Eurozone struggles with weak growth and low inflation, the WSJ reports that the number of those engaged in early entrepreneurial activity in countries like Germany, France and Italy (5%, 4.6%, and 3.4% of the population respectively) is a fraction of those in the US (12.7%). Once they are established, these businesses tend to be smaller and slower-growing than their US counterparts. They also seem less likely to hit the big time: among the world’s 500 largest listed companies, only 5 of the European firms were founded after 1975, compared with 31 from the US and 31 from emerging economies.

Digital policy analyst Adam Thierer argues that the relative performance of US and European tech firms is largely driven by the regulatory culture in each country. US policy makers have by deliberate design fostered a culture of permissionless innovation, which allows and encourages entrepreneurs to innovate, push boundaries and take risks. As a result, the American tech sector has boomed, producing inventions and companies beloved and envied across the world. In contrast, European culture has been far more risk-averse and policy far more bureaucratic. The result of unnecessary regulation and data directives has been a dearth of successful European firms. Those European ‘unicorn’ firms which strike big have overwhelmingly come from countries fairly removed from continental Europe, such as the UK, Scandinavia and Russia.

The EU’s move towards net neutrality regulation, market interventions and tighter data laws will only further disadvantage tech firms. State interference is particularly unhelpful in dynamic, evolving digital sectors, where fast-paced progress is typical and innovation key to staying relevant. Moreover, European policymakers may want to check Google’s power through legislation, but it is large incumbent firms who have the resources and lawyers to comply with new regulation. Those hit hardest are smaller competitors, and the fledgling start-ups the EU should focus on encouraging.

In some sense, European policymakers are onto something with their suspicion of ‘big tech’. The vast majority of UK internet users say that they’re uncomfortable with what they share online and with whom, and even the technophilic Wired ran a recent cover story on how the data industry is ‘selling our lives’. Perhaps people really are fed up of Google, which then only maintains its 90% European market share in search because there’s no decent alternative.

But attacking Google's influence requires innovation, not regulation. Tech history is littered with market leaders such as IBM, Nokia and AOL who have slid, sometimes quite spectacularly, from the top spot. In tech-orientated sectors it is particularly hard for large firms to stay relevant and embrace new trends – let alone to develop them.

To facilitate creative destruction and the emergence of challenger firms, Europe needs a digital policy which is favorable to new technology and experimentation, and which encourages individuals to accept risk and forge ahead with business plans without first jumping through hoops and courting regulators (the trials and tribulations of Uber and Skype spring to mind here).

Blockchain-based projects which aim to ‘decentralize the internet’ and give users more control over their data are part of an exciting peer-to-peer movement which could re-sculpt the shape of the net. But these innovators are entering unchartered territory (a wild west, if you like), and an open and permissive regulatory culture is essential in allowing them to flourish (or fail).

Were Europe to grasp this, the benefits could be enormous. But if European policymakers carry on down their current path of tightening control, we're likely to see less entrepreneurship, less competition, reduced consumer utility, and probably a lot more Google.

Don’t worry about Brand’s sexism – worry that he’s the new poster child for the left

I don’t throw around words like racism and sexism. Not because they don’t exist – on the contrary, I recognise both ‘isms’ as serious problems that plague different parts of the world to different degrees on a day-to-day basis. Racial and gender prejudices are the most heinous of crimes, and that’s why the accusation of such things must be used with thought and caution; to levy the words at a Republican voter or someone who points out the real numbers behind the ‘equal pay’ myth takes away from the seriousness of the words. I wasn’t surprised to wake up this morning, however, and read the many headlines that accused Russell Brand of being sexist. During his appearance on BBC Question Time last night, Brand got a bit carried away with the ‘confrontation game’ and wound up in hot water with his fellow, female panellists:

As communities minister Penny Mordaunt praised firefighters, Mr Brand interrupted, saying: "Pay their pensions then, love. Excuse the sexist language, I'm working on it."

This isn’t the first time Brand has been accused of ‘lazy sexism’ – he’s gotten in trouble, multiple times, for objectifying professional women he encounters, and many have noted that much of his humour stems from humiliating women in personal, direct ways.

Was last night another addition to the sexist Brandwagon? Probably not. Putting cultural differences aside, [In the States, calling any woman who is not in fact your love, ‘luv’, would be considered deeply unacceptable.] I think it’s fairly obvious that Brand was speaking casually, and arguably being a bully- but without any sexist intent. Perhaps someone should have flagged up to him (or written on that note card he seemed so attached to) that when you’re on a world-renowned platform with lots of elected officials, you try a little harder to sound more professional.

What about the other accusations? Is Brand a sexist at heart? Honestly, I don’t know. Brand’s a comedian. He makes jokes about women. Presumably he does this, not because he wants to preach his sexist manifesto, but because people laugh. Men, and women, laugh at jokes about women. Depending on the joke, I may or may not laugh along with them. Having researched some of Brand's previous jokes, there's no doubt that some of them cross the line; at which point, we should be able to get up and walk out, turn off the TV, tune him out and not give credence to his remarks.

But now we’re getting to the real problem – which is not his humour(less?) remarks, but rather that Brand, along with his jokes, have been given a huge political platform to be taken seriously by his fans and the public at large…and it’s obvious that when it comes to women, and everything else, the man has no idea what he’s talking about.

Clearly unable to come up with any stat about Britain’s population growth or housing/land availability when asked to make the case for immigration (there are some great stats out there, by the way, in favour of this argument), Brand decided to go on a loud, but not always so coherent, rant about bankers’ bonuses and why the City is ‘bad’, whatever that means. His only evidence that more redistribution of wealth would help those at the bottom was that his bank account was big enough to handle a cut, and when asked if he would actually try to put into practice what he preached (ie: stand for Parliament), the answer was pretty straight-forward: no.

This, my friends, is not just a comedian with an opinion. He is the new poster-child for the left, in the UK and beyond. He is being given the highest platforms to discuss his views and opinions, and despite his attempt at anti-establishment rhetoric, almost every policy he promotes – if you can be generous enough to call them that – advocates heavy government intervention, centralised redistribution, state-funded everything, and heavy emphasis on paternalism and left-wing policy.

Brand’s political stardom is going to backfire, but it’s hard to know who will suffer. Either, Brand will continue to slip and slide on national television, further associating the left (to their despair) with his radical, inarticulate rants; or he’ll wise up, graduate from one note card to three, cut back on the lady jokes and actually have a shot at convincing a few more people that his bank account is the only number you need to cite when reforming the UK’s buckling welfare structure. The former would be a spectacle; the latter would be nothing to luv.

Someone's lost their marbles here and it's not us

This little video by Owen Jones over on The Guardian's website simply has to be seen to be believed. It starts out with a reasonable enough analysis of property prices in London. They're high, perhaps it might be a good idea if they weren't so high and so on. At which point it might be useful to start thinking about what might be done. Perhaps more properties could be built for example, that seems a reasonable enough idea. Prices do rise when there's not that much supply and increasing supply does tend to have the effect of reducing prices. But of course this is Oor Lad Owen so someone must be to blame for this. And who does he blame? The politicians who don't seem to be addressing the problem very well? The bureaucrats who don't issue enough of the planning chitties? Us, the citizenry for having the temerity to desire somewhere to live? Nope, the enemy is apparently property developers. Yes, that's correct. The people who actually build housing are the declared enemy. He's not saying that they're just not building enough, nor that they're building the wrong type or anything. He is quite flat out stating that those who build housing are the wrong 'uns in this campaign that desires more housing. That the solution to his claimed problem would actually be to have more property developers developing more properties just doesn't seem to occur to Jones. Entirely bizarre.

But *which* right on and trendy thing should I be doing?

One of those lovely little conundrums is raising its head over in the right on and trendy food movement at present. The problem being, well, which part of being right on and trendy should people sign up to? This has actually got to the point that there's a New York Times opinion piece imploring people to, umm, well, ditch one principle in favour of another:

And yet, if you look closer, there’s a host of reasons sustainable food has taken root here in central Montana. Many farmers are the third or fourth generation on their land, and they’d like to leave it in good shape for their kids. Having grappled with the industrial agriculture model for decades, they understand its problems better than most of us. Indeed, their communities have been fighting corporate power since their grandparents formed cooperative wheat pools back in the 1920s.For the food movement to have a serious impact on the issues that matter — climate change, the average American diet, rural development — these heartland communities need to be involved. The good news is, in several pockets of farm country, they already are.

"Sustainable" food here means organic. Oh, and small producer: you know, one who cannot get economies of scale because they're running too few acres. but, you know, if people want to produce this way, live on the pittance they can earn in this manner, good luck to them and all who sail with them. and if people want to buy their produce similarly good luck. However, there's something of a problem:

But just as these rural efforts started gaining steam, an unfortunate thing happened to the urban food movement: It went local. Hyperlocal. Ironically, conscientious consumers who ought to be the staunchest allies of these farmers are taking pledges not to buy from them, and to eat only food produced within 100 miles of home.

Montana has perhaps three people in addition to all those cows. And it's a lot more than 100 miles away from any of the hipsters who are interested in small scale organic farming. And those hipsters are all eating local. Which is, don't you think, just so lovely a problem?

Those urban aesthestes are simply missing the point of farming altogether. Which is that it's a land hungry occupation (organic even more so than conventional) so it makes great sense to do that work where there's no people. Farming right by the big cities of the coasts, where land is hugely expensive (because there's lots of people in those big cities) is simply not a sensible manner of using the resources available.

Just so much fun to see the fashionable being hoist on their own petard really.

Maybe gamergate is winning

Loyal readers will remember I wrote a think piece arguing that gamergate—the loose grouping of internet gamers seen by its critics as misogynistic and by its advocates as a campaign for ethics in gaming journalism—would lose its battle against the social justice warriors (SJWs) who largely run the media, particularly games journalism. This might still be true, but a piece from Ed West at the Spectator makes me much less sure of my argument. Ed points out that gamergate—where the gamer masses are using letter-writing campaigns to get advertisers to drop support for websites like Gawker—is only the latest in a string of social justice setbacks include the Lord Freud 'scandal' and the bid to get David Cameron to wear a feminist t-shirt.

What has happened to social justice warriors recently? Every campaign seems to fail, the latest being a cack-handed attempt to police Twitter in order to win the Gamergate saga (turn to p194 for details). Gamergate is one of those things that a couple of years ago would have been resolved quickly, going into the narrative as part of the great struggle against the ‘isms’. Instead it goes on and on, and SJWs seem to be losing the battle.

He reckons that the ongoing decline of traditional news sources is giving the SJWs less of a grip on the organs of opinion-formation, democratising opinion across the internet. I'm not so sure, indeed I think the internet is rather a boon to the more virulent strains of modern social justice talk. What's more, if we really are seeing a turning point in the culture war, the small changes in internet access over the past couple of years aren't going to be able to explain it.

But I do think he has a good point about the changes of the past 20 years:

Compare the situation today with that of 20 years ago, during the greatest social justice warrior victory of all, the controversy over The Bell Curve – a big event in American and by default British cultural life. While the scientific community said one thing about Charley Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s book on intelligence, the political-media elite said another, and the public followed the latter’s lead. If The Bell Curve was published today it would be much harder for the modern-day Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to attack it.

The Bell Curve ‘war’ was an important issue in itself – as an opportunity to counter America’s growing inequality was lost. But it was also significant because it confirmed the idea that anyone who came to a controversial conclusion (in this case supposedly ‘racist’) could be ostracised, name-called and in the current parlance ‘shown the door’. That sort of ideologically-justified bullying is a key tactic of the social justice warrior movement, but when exposed as such can work against them. The nice left, after all, don’t like to be seen siding with self-appointed policemen of debate.

I recommend reading the whole thing.

Does Rupert Murdoch vet his papers' film reviews?

Media conglomerates often own newspapers and other media, while also making films, releasing music, publishing books and so on. Unsurprisingly, they are often accused of pressuring their news media to review these entertainment media more favourably than they otherwise would, and this suspicion seems quite reasonable at first blush. But a new paper finds no evidence that this is true at all for movies. "Does Media Concentration Lead to Biased Coverage? Evidence from Movie Reviews" by economists Stefano DellaVigna and Johannes Hermle say there is not even evidence of a tiny effect and suggest this means reputational effects are very important for newspapers:

Media companies have become increasingly concentrated. But is this consolidation without cost for the quality of information? Conglomerates generate a conflict of interest: a media outlet can bias its coverage to benefit companies in the same group. We test for bias by examining movie reviews by media outlets owned by News Corp.–such as the Wall Street Journal–and by Time Warner–such as Time. We use a matching procedure to disentangle bias due to conflict of interest from correlated tastes. We find no evidence of bias in the reviews for 20th Century Fox movies in the News Corp. outlets, nor for the reviews of Warner Bros. movies in the Time Warner outlets. We can reject even small effects, such as biasing the review by one extra star (our of four) every 13 movies. We test for differential bias when the return to bias is plausibly higher, examine bias by media outlet and by journalist, as well as editorial bias. We also consider bias by omission: whether the media at conflict of interest are more likely to review highly-rated movies by affiliated studios. In none of these dimensions we find systematic evidence of bias. Lastly, we document that conflict of interest within a movie aggregator does not lead to bias either. We conclude that media reputation in this competitive industry acts as a powerful disciplining force.

The whole thing is very clear in a chart—newspapers owned by News Corp are about as positive about Fox films as those owned by Time Warner (and vice versa). So much for media bias, eh!

Don't be so swift to criticise streaming

The big news in the entertainment world this week is that Taylor Swift was never (ever, ever) really that much of a fan of Spotify, and as her album 1989 takes worldwide charts by storm, she’s taken her entire back catalogue off the music streaming service. She explains :

...everything new, like Spotify, all feels to me a bit like a grand experiment. And I'm not willing to contribute my life's work to an experiment that I don't feel fairly compensates the writers, producers, artists, and creators of this music. And I just don't agree with perpetuating the perception that music has no value and should be free.

If Spotify is a ‘grand experiment’, it’s one with everyone’s attention. Its ‘freemium’ model yields 50m active users and 12.5m paid up subscribers, and Spotify royalties have recently overtaken iTunes download earnings in Europe. Other companies want in, too. Apple have recently acquired Beats in an move to host a streaming service of their own, whilst both SoundCloud and YouTube have announced plans for a premium subscription service. Streaming accounts for an ever-increasing proportion of music revenue, with consumers increasingly choosing access to a wide range of music over the ownership of specific albums or tracks.

The CEO of Spotify Daniel Ek has responded to Taylor’s commercial-cum-ethical decision, taking pains to cast Spotify as the enemy of piracy and champion of artists. It’s well worth a read, but what's interesting is the blame he levels at the wider music industry in response to Taylor’s claim that streaming fails to fairly compensate artists:

The music industry is changing – and we’re proud of our part in that change – but lots of problems that have plagued the industry since its inception continue to exist. As I said, we’ve already paid more than $2 billion in royalties to the music industry and if that money is not flowing to the creative community in a timely and transparent way, that’s a big problem.

Around 70% of Spotify’s revenue goes straight to the rights holders of the music they stream in the form of royalties, and these rights are invariably held by an artist’s record company. On average, record labels keep 46% of CD sale revenue, and 68% of download revenue. Creators receive around 9% and 8% of this revenue respectively. (Gowers Review, p.51)

At major labels at least, artists seem to receive a similar proportion of streaming royalties (and are allegedly victim to a few dirty legal tricks along the way). In addition to royalties, many labels demand advance minimum payments which can vastly exceed the actual royalties actually generated by plays, with no guarantee that artists will see any of this surplus. So whilst Spotify might pay out three to four thousand dollars for 500,000 streams, an artist might see less than 10% of that.

Of course, money isn’t really the issue for Taylor Swift, who can easily afford to take her music off of the streaming service; whilst her entire catalogue was on track to generate $6m in royalties this year, 1989 made around $12m in sales in its first week. For large artists, removing music from sites before a release or holding off streaming for a couple of months could make fantastic business sense.

But money is an issue for the majority of artists, and it's reasonable to critique what income they receive from streaming. Though some like Swift, David Byrne and Thom Yorke attack streaming for what they consider meagre payouts per play, they'd be better off focusing their attention not on the upstart ‘disrupter’, but the entrenched music industry which Spotify claims it is actively trying to save.

Spotify certainly has a challenge there. The size of the streaming industry is currently nowhere near big enough to compensate for the long-term decline in physical (and now digital) sales. And whilst it is growing rapidly, Spotify is yet to turn a profit in its 6 year history. This is largely a problem of scale, as the more users and the more plays the company attracts, the more it must pay out in royalties. Some analysts think it just needs more users to pay up. Others worry that the high proportion of their revenue forked over to rights holders makes them intrinsically unprofitable. In this scenario, streaming services might simply become loss leaders for larger companies like Apple and Google, or get taken over by the music labels themselves. In which case, perhaps Thom Yorke is right that streaming is the “last desperate fart of a dying corpse” after all.

But what part of the music industry is dying, and is it really worth saving? The entrenched record labels and collecting societies have long warned that technological advances, piracy and copyright infringement are destroying the livelihoods of creators. They expend significant time and resources lobbying for government protections like DRM and copyright extensions, multinational treaties like ACTA, and forcing ISPs to police their users' activities. Yet if you look past these vocal and influential legacy organisations, the music industry is actually flourishing. A study by Mike Masnick points out that the global value of the broader music industry has grown from $132bn to $168bn between 2005 and 2010. The number of new albums produced each year is rising rapidly, concert sales tripled over the past decade in the US and entertainment spending as a function of income has risen by 15%.

The music scene is evolving, and with the low costs of digital production and distribution becoming more competitive. There’s going to be some who lose out and see their old business models change. Certainly, Spotify alone cannot revive label's revenue to the heyday of CD sales, and nor is it their responsibility to. But it is shortsighted to suggest à la Taylor Swift that to stream music is to consider it valueless. And if artists are concerned by the lack of revenue reaching them, the best place to start complaining is to their own labels. The growth of the music ecosystem in non-traditional areas shows that they're already lagging behind the times despite all their billions in intellectual property, and it would be such a shame to see them have their breadwinners turn against them, too. I for one wouldn’t want to feel Taylor’s wrath.

The deep web, drug deals and distributed markets.

On Thursday a conglomeration of law enforcement agencies including the FBI, Homeland Security and Europol seized the deep web drug marketplace Silk Road 2.0, just over a year after the takedown of the original Silk Road site. San Franciscan Blake Benthall was arrested as site's alleged operator (under the alias ‘Defcon’), and charged with narcotics trafficking as well as conspiracy charges related to money laundering, computer hacking, and trafficking fraudulent documents. The authorities allege that Silk Road 2.0 had sales of $8million each month, around 150,000 active users, and had facilitated the distribution of hundreds of kilos of illegal drugs across the globe. The bust formed part of ‘Operation Onymous’, a ‘scorched-earth purge of the internet underground’ which led to the arrest of 17 people, the seizure of 414 hidden ‘.onion’ domains, and the shutdown of a number of other deep web markets. Law enforcement unsurprisingly refuse to reveal how they managed such a raid, leaving to some worry that they have been able to bypass the protections of the anonymizing software Tor, which is used to access deep web sites and to obscure users' identities and location.

Despite the success of Operation Onymous, many deep web markets remain online. Activists liken the shutdown of hidden marketplaces to a hydra: every time a site is taken down others spring up in their place, and thrive from the media publicity of busts. Indeed, the number of drug listings on hidden marketplaces has grown significantly following the takedown of the original Silk Road. Regardless, law enforcement is determined to stamp out the sites, with a representative from Europol warning “we’re a well-oiled machine. It won’t be risk-free to run services [like these] anymore’.

But what if there was no-one responsible for running such services? Sites like the Silk Roads met their demise because they have a centralized point of failure — get to the server and you can seize the site. Allegedly, cryptographic chunks of Silk Road 2.0’s source code had been pre-emptively distributed to 500 locations across the globe, to enable the site’s relaunch in the case of a takedown. Given the far-reaching impact of Operation Onymous, whether this happens or not remains to be seen.

To be truly immune to government takedown, a marketplace would have to have a decentralized, distributed structure, much like torrent networks and the bitcoin protocol. Enter OpenBazaar, which uses peer-to-peer technology to bring 'secure, decentralized markets to the masses.' In running the OpenBazaar program, each computer becomes a node in a distributed network where users can communicate directly with one another. A reputation system will allow even pseudonymous users to build up trust in their identity, and naturally, all transactions are done in bitcoin.

The biggest issues plaguing hidden marketplaces are those of trust and enforcement; if goods or payment fail to materialize, you can hardly just contact the authorities. Some sites get around this problem by offering an escrow service, with the money being centrally held until a buyer confirms their goods have arrived. The problem with this approach is that it leaves customer's money vulnerable to scams, hacks, and state seizure. With a decentralized system like OpenBazaar, no such central escrow system is possible. Instead, buyer and seller nominate a third party 'arbiter' (who could be another buyer, seller, or a professional arbiter for the site) to preside over the transaction. Payment is initially sent to a multi-signature bitcoin wallet, jointly controlled by the buyer, seller and arbiter. Funds can only be released from this account to the seller when 2 of the 3 signatories agree to it, allowing the arbiter to adjudicate any dispute.

In such a distributed system, there’s no central body to authorize posts and transactions. There’s also no central server to target. Law enforcement would have to go after all buyers, sellers and computers running the OpenBazaar software to bring the system down.

OpenBazaar is still in beta mode, with a full release expected in early 2015. Teething problems are likely and the design could prove problematic; even within highly decentralized systems there’s a tendency towards the concentration of power, and whilst robust, decentralized networks are often inefficient and expensive to maintain. There's no doubt the authorities are watching, though, and it will be interesting to see their reaction should OpenBazaar succeed.

The software is a re-work of the edgier DarkMarket concept developed at a Toronto hackathon earlier this year, and its developers are keen to highlight its use for selling things like outlawed books and unpasteurized milk over drugs and guns. Certainly, there's value in any global bitcoin marketplace which avoids punitive exchange rates and transfer fees, and like the Lex Mercatoria, can be relied on to provide a level of transactional security when state institutions can not. However, whatever its legitimate uses no state will be comfortable with the idea of a censorship-proof site. The problem for them is that they might just have to get used to it.

Is Gamergate a classic case of left-wing infighting?

I published a 'think piece' on gamergate over at the research side of the website yesterday. I argued that the pro-gamergate side was likely to lose because the left usually wins (for good or bad) on cultural issues:

Gamergate is one of the most interesting cultural issues that has appeared in years. It is a rare time that the losing side of the culture war has put up a good fight. But the anti-gamergate side will win, because Progress always wins. I’ll try and give a concise guide to gamergate, what’s at stake, where it came from, and why exactly it is that it will lose.

I read another good post on it from Cathy Young over at realclearpolitics—she made a different point to mine, trying to stress how it was not reasonable to characterise much of the movement as anti-women or misogynist, but simply taking an alternative (and she believes, valid) approach to improving the lot of women in gaming:

There are valid concerns, shared by at least some GamerGate supporters, about sex-based harassment in gaming groups and stereotypical portrayal of female characters in videogames. Unfortunately, critics of sexism in videogame culture tend to embrace a toxic brand of feminism that promotes antagonism, grievance, and intolerance of dissent, not equality or empowerment.

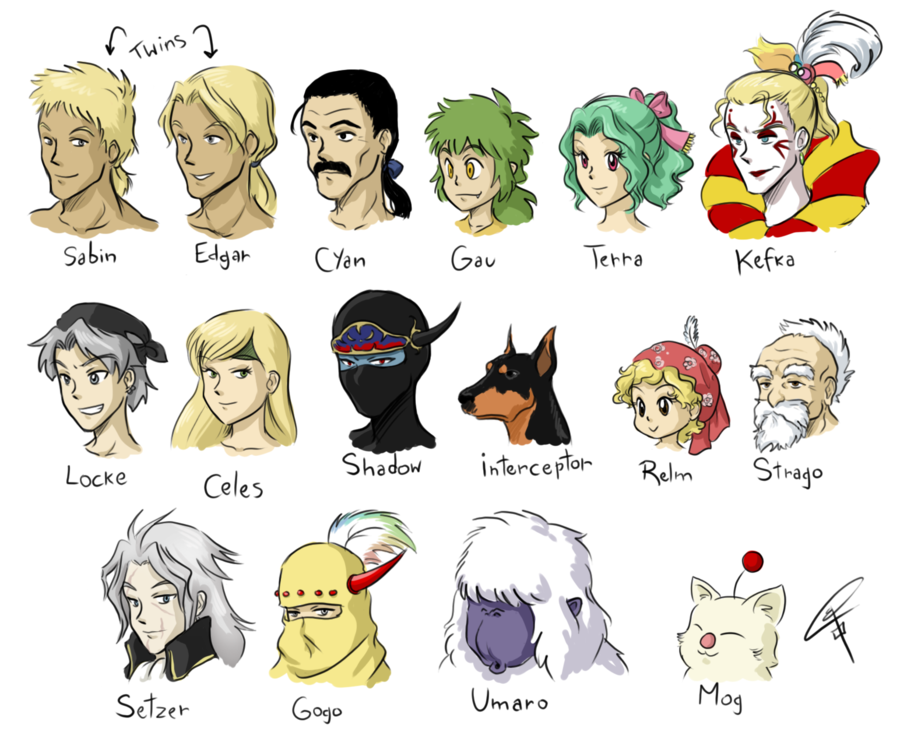

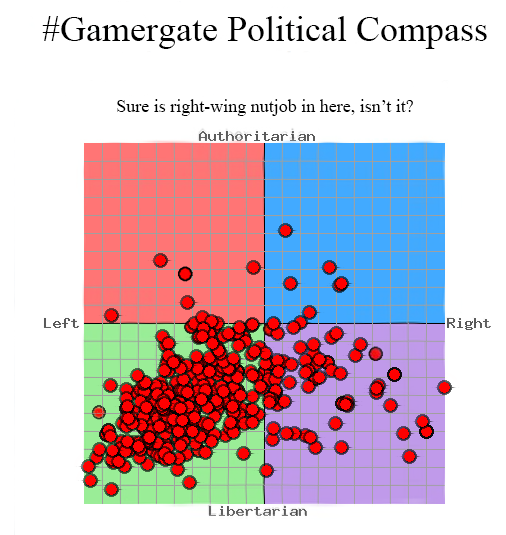

When I posted my piece on twitter I asked for constructive criticism, and one good point that was made is that, at least according to their own views of themselves and their results on political compass tests, gamergaters tend to lean left.

This makes me think that gamergate might be best characterised as a case of leftist infighting, but this time between Murray & Herrnstein's 'cognitive elites' that make up social justice anti-gamergate journalism and the broader constituency of more 'normal' pro-gamergate leftists holding more traditional leftist views. An open front in the war between New and old versions of what justice consists in.

This fits with my anecdotal experience that it is those (like Richard Dawkins) who are or have been associated with the left that experience most of their ire when they state or are suspected of having unacceptable views. As ever it's interesting to look at the parallel with religion, which abhors apostates much more zealously than infidels.

And it also fits with the modern left's de facto focus on race, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability as opposed to their previously overwhelming concern with economic exploitation or justice. As I said in the think piece:

Bear in mind that although social justice advocates do care about wealth disparities, this is far from their main concern, at least in terms of how they allocate their time. For example, insufficiently pro-transgender feminists will arouse large campaigns stopping them from giving lectures at many universities, while libertarian capitalists can speak freely. This is why I have argued that social justice is (a) a facet of neoliberalism, and (b) an artefact of the cognitive elite’s takeover of society. This is what makes the modern social justice movement so different.

This ends up working quite well for the ASI: we are quite comfortable with social progress as long as it allows for liberal economic policy, and only tend to object when social progress conflicts with more important goals such as free speech.