Seven reasons not to care about high pay

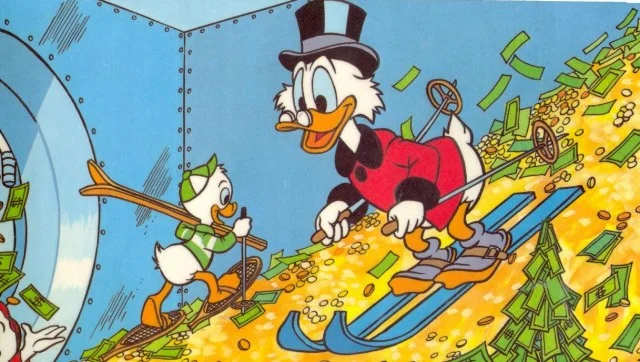

- Executives can be worth a lot to firms. When bad CEOs are sacked or new CEOs who are expected to be good are hired, the firm they work for can become a lot more valuable. Apple lost 5% of its value after Steve Jobs died, about $17.5bn. Microsoft became 8% more valuable after Steve Balmer resigned in 2013 – he represented more than $20bn worth of losses to Microsoft. Angela Ahrendts's departure from Burberry in 2013 wiped £536m off the firm’s value; Tesco became £220m more valuable when its CEO merely announced that he would take an active role in managing the firm. Why? Because CEOs make really important decisions that can make or break the firm.

- Critics of high pay can’t say how much they think CEOs should be paid. The High Pay Centre says it thinks CEOs are paid too much, but how much would be the right amount? They don’t say, and don’t suggest any real way of knowing. They emphasise multiples of employee pay on their website, but there’s no reason at all to think that would be a good way of judging how much a CEO is worth to the firm, and doesn’t even make sense across firms – is the CEO of a giant firm with a low average wage, like McDonald’s or Tesco, less important than the CEO of a relatively small firm with a high average wage, like QinetiQ?

- CEOs might be much more important now than they were in the 1960s. The most interesting question about executive pay is: why has it risen so much since the 1960s compared to median worker pay? There are a couple of different reasons this might be. One, as Scott Sumner suggests, is that CEOs actually are much more important now than they were (so being a good one is more valuable to a firm). Executives’ decisions probably mattered less when the world was less globalized and markets were less diverse – you knew what sorts of appliances and groceries consumers wanted, and your job was to manage capital competently to produce them. Now, even big firms face rapid destruction if they make the wrong call about what sort of products are going to popular in a few year’s time. As Sumner says, “Think how much Sony would have benefited in the past 10 years if it had had the Samsung management team”.

- …But tax and regulation probably plays a role too. Economist Kevin Murphy argues that history of executive pay (particularly in the United States) is only understandable in the context of tax and regulatory changes, like penalties on golden parachutes, a rise in stock option grants caused by changes to tax and accounting rules, and “changes to holding and listing requirements that favored stock options over other forms of incentive compensation”. (NB: This doesn’t mean that these rules are bad or undesireable, but they may help us to understand why executive pay is higher now than it once was.)

- Performance related pay causes executive pay packets to rise on average. Critics of high executive pay often call for pay to be more closely linked with performance – in the form of stock rewards, for example. But as Murphy shows, this actually makes the ‘problem’ of CEO pay even worse, because pay has to rise on average to reflect greater risk. “The payoffs from stock options, for example, are inherently more risky than are payoffs from restricted stock, which in turn are more risky than base salaries.” So the more we try to make CEO’s pay reflect performance, the higher CEO pay will be!

- Employee representation can be bad for firms. The High Pay Centre’s policy prescriptions are quite modest – today they’re calling for firms to include a worker representative on remuneration committees, which doesn’t sound like a big deal. And it probably isn’t. But employee representation on boards can be a very bad thing: according to a Financial Times report on Volkswagen last year, worker representation on the car company’s board turned the board atmosphere toxic, and led to very bad decisions being made. Reform of bad practices was blocked by the employee-supported Chairman, who worked against shareholders and his own Chief Executive to stop jobs from being cut and working time limits from being raised, ultimately harming the firm. Strangely, the High Pay Centre cites Volkswagen as a success story.

- It’s shareholder money on the line. Ultimately, it’s hard to see the public interest argument here. If shareholders are really missing a trick and overpaying their chief executives, who loses out? Well, shareholders, in the form of lower profits. And they’re the ones who stand to gain if they can fix that problem. Unless the High Pay Centre can show that the market is completely broken (and pointing to high pay as evidence for this is circular reasoning) there must be an opportunity for a firm to realize that CEOs are being overpaid, to buck the trend, and presumably to prosper. Why hasn’t that happened yet?

Minimum wage debate: still not over

The new round of NBER papers is, as ever, interesting. One of particular interest comes from Jeffrey Clemens at the University of California San Diego. He refreshes the minimum wage debate by dialling in on the effect of hikes (a) during the great recession and (b) on lower-skilled individual aged 16-30, finding a fairly substantial effect on that group.

I analyze recent federal minimum wage increases using the Current Population Survey. The relevant minimum wage increases were differentially binding across states, generating natural comparison groups.My baseline estimate is that this period's full set of minimum wage increases reduced employment among individuals ages 16 to 30 with less than a high school education by 5.6 percentage points. This estimate accounts for 43 percent of the sustained, 13 percentage point decline in this skill group's employment rate and a 0.49 percentage point decline in employment across the full population ages 16 to 64.

The debate is not over, but this does look like a reminder that there's 'no such thing as a free minimum wage hike'.

In memory of Jimmy Hill, let's stop calling for maximum wages

Vale Jimmy Hill: and in his memory perhaps we can stop this incessant whining for maximum wages emanating from over on the left. Before his campaigning footballers were the hired helots of their clubs: after it they became the major beneficiaries of the money flowing through it. All rather Marxist, and why not, the profits and value of the business flowing to those working by foot and head:

In 1957, Hill, then a bossy midfielder with Fulham, was elected chairman of the Professional Footballers Association (PFA), the players’ union. At the time the maximum weekly wage for footballers was capped at £20, although the best teams could draw crowds of 60,000 every Saturday afternoon. Stars such as John Charles were being tempted to leave the British game for Italy, where there were no limits on pay, while some clubs were paying illicit bonuses to players to persuade them to stay. The confrontation between the Football League and the PFA began when the former suspended some Sunderland players suspected of taking under-the-counter payments. Hill worked successfully to have them reinstated, and then challenged the League to end the wage cap and to allow footballers to move freely when their contracts ended. Astutely using television to win over public opinion, Hill – who always had something of the barrack room lawyer about him – took his union to within four days of an all-out strike in January 1961 before the League was forced to capitulate. The lid of Pandora’s Box had been forced open, and football would never be the same again.

British football is certainly different and almost certainly vastly better for the change. It would certainly be difficult to see what would be left of it if wages were still capped at around those of a skilled working class job.

This is not just about footballers of course: parts of Wealth of Nations are Smith railing against the wage and price fixing of the medieval guilds, and how those distort an economy to the detriment of the consumer.

We do not want to have price fixing of any kind, because prices are signals about how scarce resources should be used to best effect. If that means that rare skills, from nutting a leather ball to running a 100,000 person corporation bring in large incomes (and the two are, these days, comparable in amount) then so be it. As long as the result comes from a free market in skill and talent and not from rent seeking then that's the best allocation of talent we're going to get.

The financial ignorance of the British left

We shouldn't let these things surprise us but, if we're honest, we have to say that every time it does it surprises us. Such a thing being that we find ourselves in disagreement with someone over some point or policy: that's fine, there's many different ways of looking at the world and we wouldn't claim a monopoly on all of the good ones. But as we examine the disagreement we find that it's not one about morals, or end goals, or a conception of the world that we don't share. It's based upon the sheer deluded ignorance of the person disagreeing with us. As you might imagine this happens when discussing matters economic and financial with the British left. Such a case is here, from Compass:

Key British assets which bring in millions of pounds worth of profit and provide incalculable social benefits are to be sold soon if the chancellor gets his way. Buried within the recent Spending Review are plans to sell off billions of pounds worth of public assets: the Land Registry, National Air Traffic Services (NATS), the Green Investment Bank, bailed out banks RBS and Lloyds, and the student loan book amongst others.

OK, we agree, there can be differences of opinion on such things. You could, for example, be a union leader who thinks that your members will get an easier deal in the public rather than private sectors. And given that that's what you're there for, to get the best deal for your members, we wouldn't blame you for making some sort of argument. Disagree with you, obviously, but not blame you. But that's not the argument that is being made, instead we get this delusion:

The other assets up for grabs are making a profit in public hands and would continue to return money to the public purse for years to come. NATS returned £82 million back to the public last year. Through Britain’s 49% stake in the service, we sell services to airports and airlines in 30 countries, generating £157 million in pre-tax profit in 2014. The Land Registry currently has a 98% customer satisfaction rating, and returned £100 million to the Treasury in 2013. Ordnance Survey made £32 million profit in the past year, and its data underpins £100 billion of the economy.

If these assets are sold, it doesn’t take an economist to realise that future governments will face a significant loss of revenue, thereby making it harder to invest, protect its citizens, plan ahead, and keep to a sustainable economic path.

Perhaps an economist should have been consulted before that statement was made (perhaps a financier too: who would buy Land Registry in order to stop producing the data that underpins £100 billion of the economy?). For of course the government is considering the sale of these assets, not their gifting to someone. And the persons they are sold to will, to introduce a new word, "buy" them from the government. That is, they will hand over a capital sum now in order to be able to enjoy those incomes into the future. And government will gain a capital sum now instead of the income streams off into the future.

And the price at which this bargain is struck will be at or around the net present value of those future income streams. Just because that's how assets are valued in this world of ours.

What worries is not that people differ with us on the advisability of this idea, it's that the people complaining have no clue what the idea is in the first place.

The contention is that we convert a future income stream into a capital asset now, that value being that of the net present value of the future income. Or is that too complicated for the British left to understand?

Proof that regulation is not needed used as proof of the desirability of regulation

This is a rather alarmingly bad piece of logic from a prestigious source:

The Committee employed investigators to collect data from the munition plants and to conduct surveys of the health of the workers. From the data collected, the Committee made a number of recommendations including mandatory shorter working hours, the avoidance of continuous night shifts and, above all, giving workers at least one full day off from work each week.This study revisits the data collected by the Committee’s investigators and determines whether the Committee’s recommendations are supported by this new examination. It finds the Committee’s recommendations fully justified. For example, with respect to the value of one day off work each week, Professor Pencavel calculates that the week’s output was slightly higher when these munition workers worked 48 hours over six days than 70 hours over seven days.

Excellent. So there's an optimal length to the work week then. All work and no play produces not just dullards but lower output.

So, what would we expect a profit making employer to do then? Correct, try to determine where that optimal work week length was and then employ people for that period of time. But what does our professor suggest instead?

‘Instead of viewing restrictions on working hours as harmful restraints on management, statutory regulations on hours may serve as an enlightened form of enhancing workplace efficiency and welfare.’

He's using the proof that a profit maximising employer doesn't need such regulation to argue for such regulation.

Most, most odd.

Markets can see the future

One argument that monetarist economists like myself often make is that what matters is not so much the central bank's policy now, as what the central bank is expected to do in future years. The Bank's base rate might be low right now, and the Bank may hold rather a lot of government bonds in a big quantitative easing programme—but if it's expected to offload the gilts and hike rates tomorrow, markets will react today. Macro conditions are tight now if monetary policy is expected to tighten soon. A new paper (pdf) from Stefania D'Amico and Thomas B. King of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and entitled "What Does Anticipated Monetary Policy Do?" tackles this question empirically, looking specifically at 'forward guidance' over rates—where central banks tell markets they will keep policy interest rates at a certain level for a certain amount of time in the future.

They use a methodology similar to earlier papers, including one that I wrote about earlier, using surveys of financial market actors to work out whether a given change in rates (or planned future rates) is a shock or not.

They identify this difference by looking at expectations of inflation and GDP. If lower forward rates coincide with lower expected inflation and GDP, they reason that rates are being lowered to counteract some external factor driving inflation and GDP down. If lower forward rates coincide with higher expected inflation and GDP, they reason that the rate lowering signals an easier monetary policy overall, higher future aggregate demand, and thus higher nominal variables (and if there's any demand deficiency, higher real variables).

It's the second kind—where rates and inflation/GDP move in opposite directions—that signals a change in policy. And this policy change, according to D'Amico and King's data, feeds through into real outcomes. Promising easier policy does lead to easier conditions now—raising inflation and real GDP right away—and in fact it does so substantially. In their own words:

We find that when survey respondents anticipate a monetary policy easing over the subsequent year (controlling for past macro data and the current policy stance), this leads to an immediate and persistent increase in both prices and output.

For example, a decrease of 25 basis points in expectations for the average short-term rate over the next year, holding all else constant, results in a short-run increase in both GDP and the price level of about 1 percent.

These effects occur much faster than those of a conventional monetary-policy shock, which we identify in the same VAR. After about two years, a given shock to policy expectations has about the same effect on output as a conventional policy shock of the same size and an effect on inflation that is 2 to 3 times as large.

Shocks to expectations beyond the one-year horizon still have effects in the same direction, but they are smaller, less persistent, and not always statistically significant

Now, this doesn't necessarily mean we want central banks to do forward rate guidance. We might reasonably want them to get out of the business of setting any of the lending rates in the economy, and simply adjust the supply of money to meet demand, as private banks would do under a free banking system. But this does give us an extra reason to be wary of fiscal policy in slumps—monetary policy is enough.

It's great that we've got Dickensian working conditions these days

Felicity Lawrence is trying to tell us, over in The Guardian, that working a pretty bad job in a Sports Direct warehouse is equivalent to Dickensian times. Total nonsense, of course. For the only people asking for another bowl of gruel these days are the Islingtonistas who scoff down the Italian equivalent, that polenta pictured above. That the cheap (and disgusting) sustenance carbohydrate of the masses is now eaten by no one at all other than fashionistas shows us quite how far we've come. However, there's a deeper mistake that she makes:

Sadly, the Sports Direct warehouse is not an aberration. Much of the growth in employment of recent years has been in this field: jobs that in fact represent the death of the real job. The idea that a company’s value and brand is built not just by its owners but by the labour of all its workers has become a lost paternalistic dream. The notion that staff should be rewarded for their part in success with a fair share not just of profit but of security has all but disappeared. The risks of doing business, traditionally carried by capital, have been pushed down to those who can least afford them.

Yes, that's exactly how we want it too. No, not because we're siding with the plutocrats but because anyone at all with the ability to see can note that this last recession was somehow different. Where did all the unemployment go? Given the fall in GDP we would have expected a rise in unemployment to perhaps 4 or 5 million. As many did in fact predict and as did happen (and very much worse) elsewhere. Instead, in the UK, productivity and wages fell.

The answer is at the core of the Keynesian (and New K) analysis. Wages are sticky downwards: thus, in a recession, when labour needs to become cheaper relative to what it produces, we get spikes of unemployment as that's the only way that wages do indeed fall. And this time around this just didn't happen. Incomes took the hit, not employment. The result being that we must conclude that we have a much more flexible labour force, that wages are less sticky downwards.

This is generally thought to be a good thing. In bad times, that all or most lose 5% of their incomes could be, if that's the way you want to look at it (we do), considered to be better than 5% of the people losing their entire incomes. So, that's how the labour market has been rigged. So that it is incomes and wages that take the minor hit, not some subset of the population that take the major unemployment hit.

Profits and capital income also fell, by much more than those labour incomes, so it is shared pain, not entirely loaded on one side or another.

But that is the choice that has to be faced. We either place all the risks of busts on capital, in which case we risk soaring unemployment in such busts, or some part of it is placed upon flexible labour and thus some part of the pain is felt in minor losses of income.

Well, which do you prefer? And you can only choose one of those two, there are no others available to pick from.

Trade body head doesn't like new rules which deprive trade body members of income

Now this is a surprise, isn't it?

The UK’s accountant-in-chief has issued a stark warning that new rules designed to cut red tape for small businesses could increase the risk of crimes going undetected and reduce public trust in British business. From next year, businesses that turn over less than £10.2m a year will no longer have to get their accounts independently signed off by an auditor, raising the limit from £6.5m. The change – part of Business Secretary Sajid Javid’s push to slash regulation for UK companies of all shapes and sizes – will lift an estimated 11,000 businesses out of audit requirements, and means that 98pc of Britain’s businesses will not have to carry out a full audit.

So, how should we evaluate this?

However, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) last night cautioned that the decision would leave companies vulnerable to fraud, money-laundering and inaccurate tax bills. Michael Izza, chief executive of the ICAEW, said the body, which represents almost 130,000 accountants across the UK, is holding talks with the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills about its fears.

Hmm.

“We understand their concern is to reduce the regulatory burden on business, and this is an aim we fully support. We just believe the savings would be better made in less potentially damaging areas,” said Mr Izza, who has in the past chaired a number of Treasury working groups. Bodies such as the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants have said raising the threshold to £10.2m would risk the livelihoods of many small and sole-practitioner auditors.

Well, you are free to think what you wish of course but we would evaluate this in the following manner.

These trade bodies are no more and no less than the trade union for the profession involved. Their point and purpose is to make sure that their members get as much as possible out of the hides of the rest of us. Just because they are professionals rather than horny handed sons of toil does not change this in the slightest whit.

The accountant's body shouting that more accountants must be employed is no more of a surprise than PCS, the taxmens' union, paying people to write reports shouting that more taxmen must be employed, should shock as little as the teachers' unions arguing that teacher pay should be higher, is as much news to society as freelance writers bemoaning their rate of pay is.

They're out for themselves, all of them, and as long as we remember this we can value their contributions to debate properly. That is, we should ignore them. They are arguing that more of your money should be in their pockets. And?

Higher tax rates mean less social mobility

Don't believe me, believe the empirical academic research! When economists finish their PhDs and are looking for a job they produce a job market paper. Given the incentives here, these tend to be particular impressive pieces of work, whether in method, data, estimation or topic, and this from Mario Alloza at UCL (his website) is no exception.

The paper (pdf) looks at changes in tax policy in the US and a representative sample of households between 1967 and 1996 and finds that a 1¢ in the $ rise in marginal tax rates leads to a 0.5%-1.3% decline in the probability of someone's changing income decile. For example, moving from being in the bottom 10% to being in the 10% who earn more than the bottom tenth, but less than everyone else.

According to Alloza's data, this effect is particularly significant at the bottom of the distribution—i.e. for the poorest people—and comes because taxes affect work incentives. When taxes are higher, that reduces the benefits to badly-off people from working harder and more and changing their prospects.

He says that we his result should make us more cautious of raising taxes to reduce inequality, because it will reduce opportunity and social mobility:

These empirical results have important implications for the design of fiscal policy. Tax reforms that reduce marginal rates are more likely to increase equality of opportunity (as measured by the degree of income mobility). This is because an attenuation of the distortionary effects of taxes in the labour market would make households more likely to take advantage of economic opportunities and move up in the income distribution. Therefore, fiscal policies that aim to reduce inequality should weight the trade-off in households’ welfare induced by the effect on income mobility.

Indeed, given all the costs of caring about inequality, and the very meagre benefits we gain from ameliorating it, perhaps we shouldn't care about it at all.

There are times we despair over human intelligence

So our intrepid traveler goes off to Cuba, just to see what it's like. And he notes that no one has any money, everyone's dirt poor. And there's not really much of anything to buy with the money that people don't have. Also, the food is, to be polite, not great, tasting old and stale and frankly, there's better Cuban food at Miami airport. And there's a shortage of toilet paper and you'll really never find soap. And the best part of the trip was:

Is it true there’s no advertisements anywhere?

Yup! This was the coolest part. An entire week and a half of not being sold to by huge corporations. The only ads we saw were the aforementioned Socialist propaganda billboards on the side of the road.

The absence of those huge corporations being why you can't wipe your bottom, nor wash your hands afterwards, nor even get fresh and decent food to put in the other end. Nor, of course, the jobs, production or money to purchase that cornucopia of things that huge corporations produce.

Billboards reading "everything is for more socialism" are much cooler than anyone actually having anything.

We console ourselves with the idea that intelligent life might one day arise on this planet. Perhaps.